By now those of you who routinely read my blog know I love translations. Mainly because I need the practice, but also because I find little gems I absolutely adore and wish to share. Today found Maurice Sceve who oversteps the time boundaries of medieval literature, but only by a smidgen. I find his work fascinating for several reasons, but most notably for his introspective examinations of the physical and simultaneously spiritual reworking of Petrarchan impossible love that he exemplifies through his (perhaps most famous poem) “Delie.”

Multiple speculations exist as to the true identity of his lady, but most concur that it was the fellow poetess Pernette du Guillet. My interest here recalls the mal mariee poems from centuries before, but inverted. I find his verses an odd mixture of the displeased female voice intermingled with the promising male suitor where Petrarch meets the Trobairitz (if such a meeting had been possible).

Background wise, he writes in Lyon during the sixteenth century, which was indubitably the most creative period in the city’s history up until then (which is to say it is still an amazing city). Lyon was at that point considered as cultured as Paris, and housed a mixture of literati familiar with and under the close influence of the latest Italian trends, treading between Petrarch and Marot.

“Delie” had a mixed reception that lasted hundreds of years where the poem was for the most part considered nonsensical and unreadable. However, its obscure wording intrigued readers and remained within the public conscience – by the twentieth century it gained prominence for its psychological beauties resonating with modern sensibilities.

“Delie” as a whole is a part of a much larger cycle of 449 stanzas, but this piece which I shall translate is only a single dizain, a ten line strophe, that within its brevity is identified with the Greco-Roman Delia, an amalgam of Diana, the goddess of chastity, and Hecate associate with many things, amongst which is the moon. The former’s hunting weapons are here translated in the arrows of love, or blazes, and the later’s rays illuminate the night, or darkness, of the poet’s ignorance.

Quand l’oeil aux champs es d’esclairs esblouy,

Luy semble nuict quelque part qu’il regarde:

Puis peu a peu de clarte resjouy,

Des soubdains feuz du Ciel se contrgarde.

Mais moy conduict dessoubs la sauvegarde

De ceste tienne, et unique lumiere,

Qui m’offiusca ma lyesse premiere

Par tes doulx rays aiguement suyviz,

Ne me pers plus en veue coustumierie.

Car suelement pour t’adorer je vis.

When the eye in the fields is dazzled by lightening,

It seems it finds night wherever it looks:

Then little by little it regains clarity,

Against the sudden blazes of Heaven it guards itself.

But I, navigating under this protection,

Of your unique light,

That obfuscated my first joys,

By your sweet sudden rays of light,

Am no longer lost in ordinary sight

For solely to love you I live.

The title is suggestive of even more, and serves as a play on words for Delie – l’idee – the idea of woman. The idea of course bears the connotation of platonic ideas that rely on a form, or image of an ideal, rendering Delie the ideal woman (and quite nicely the anagram is not lost in translation as Delia works into ideal). Yet, Delie’s historic references in context bring into question the type of woman celebrated by society and considered this eponymous ideal. She shares a name and identity with females known for their chastity and aloofness. While Diana and Hecate are often conflated due to their various similarities and overlapping attributes, which in itself is telling, I am mainly focusing on certain overarching symbols here that can encompass both women without necessarily negating their individuality.

Returning to the poem, Delie, the chaste and aloof mistress takes on yet another nuanced identity that can also be attributed to the fore-bearers of her name – mysticism. Diana and Hecate (along with Luna) were relegated to a single sphere based on their ability to influence women via their manipulation of the moon, an entity already thought to be inconstant. Thus Delie’s ever changing countenance simultaneously dazzles, shines, and blinds the speaker – beckoning him with her sweet rays while conversely like a siren who relies on sight over sound, “blazes” the poet’s eyes. So far the ideal woman is not winning many awards.

I love how the entire dizain plays with the imagery of light and various measures of it. We first encounter light in the first two lines where it is so brilliant it blinds, relegating sight to darkness, such as is the case when a person walks from a darkened room into bright sunlight only to be left unable to see and perhaps even in pain. Recall in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” where sight, meaning exposure to a higher truth, rendered the man overpowered by his senses. Here too the speaker of the poem finds himself overcome by the light, or the supreme truth, of Delie.

Further, the poet’s imagery continues in an almost deliberate attempt to position himself as a vessel to receive Delie’s light in a range of intensities. The differences in intensity draw on medieval theories of light that originated from biblical scriptures and liturgical commentaries. Light was divided among several categories delineated by the relationship between receptor and source. External light, coming from nature, and in the case of our poem, the moon, is ordinary, unprocessed and practically profane. The eyes of the poet act as the receiving party and also an almost sacred boundary that functions to cleanse this untamed light. Thus by the third and forth line the eyes guard against sudden blazes, or unfiltered light, and regain clarity through such purging.

By the end of the short poem this light has crossed the borders and resides well within the poet’s eyes, serving as the primary source of divine inspiration, elevating the mind and renewing the spirit. Thus here the ideal woman straddles the realm between temporal and spiritual boundaries, and from the perspective of the poet, guides his soul towards betterment. I find the distinction between the speaker’s and the reader’s interpretation of the ideal woman to be most interesting. Her ephemeral qualities render her utterly unappealing, but when looking at her through the eyes of the narrator she is redeemed by her light, or inner workings that speak to a greater entity. Any harshness her light gives off as she dazzles and blazes can be considered a kind of sandpaper that chisels away impurities from the speaker’s soul.

Lastly, this focus on light is ultimately tied in with optics, and I think it would be worth exploring the implications of this seeming inverted gaze; the male gaze is deflected by Delie’s rays of light, and through an act of refraction it transforms into an almost feminine gaze while still mediated through the male voice via the speaker.

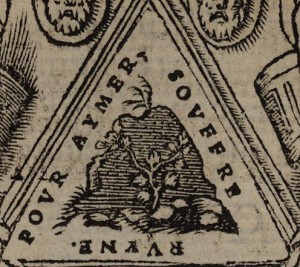

And on a separate but not completely unrelated note, the manuscript containing the entirety of Delie (all 499 dizains), Bodleian Library Douce S35, also contains 50 woodcuts. All of them interact with the text, and the mise-en-page betrays a symmetry that I feel eerily reflects the recurring theme of sight/light/ and reflection/refraction – perhaps an interesting foray into the idea of mirrors and and their uses.

In the meantime, here are some of my favorites for the manuscript:

(the figure on f. a8r has a man below a flame on what appears to be a pedestal, and the inscription along the sides of the diamond border reads: Pour te adorer je vis – for to love you I live).

(f. b6v – figure depicts a sun and a candle, and the inscription on the inside of the oval boarder reads: A tous clarte a moy tenebres – All clarity to me is dark)

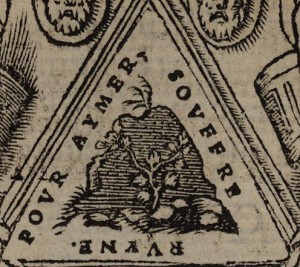

(f. e4r – detail of this figure is represented below, and the writing along the side of the triangle boarder reads: Pour aymer souffre ruyne – For love, suffer ruin)

(f. e4r – detail)

Since the pictures I am posting here are not the best quality and awfully fuzzy, here is the link to the entire manuscript should you wish to look at the rest of these marvelous woodcuts.

Sources:

Balavoine, Claudie. “La mise en mot dans la Délie de Scève. Plaidoyer pour une anabase.”

Coleman, Dorothy. “Les emblesmes dans la Delie de M. Sceve.”

Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain. Musee nationale du Moyen Age, Thermes de Cluny. Guide to the Collections.

Sceve, Maurice. Delie, 1544, with an appendix from the edition of 1564; introductory note by Dudley Wilson.

O’Neil, Edward. “Cynthia and the Moon.”