Tonight I found myself asking the question “what is an author?” and this question came at me two fold where, as a scholar, I had a grasp on the gravitas of such an inquiry and was able to discern the proper theoretical implications, while simultaneously asking this question from a far more naive position that presumed nothing and genuinely, and very simply, wanted to know “what is an author?”

It was actually the simplicity of it that was the most startling as I fumbled to begin defining authorship. For those of you familiar with my work, especially with the French female writing (the trobairitz and the female scribe of the Lancelot post-vulgate cycle) I wrestle with this term quite often and just as often feel as though I have defined it somehow, or at the very least have breached into it sufficiently for dissection. I have carved out pieces of the term for my own use and have applied my acquired definitions of authorship across spectrums of writing believing to have defined aspects of textual activities.

As far back as in undergrad most of us were taught that authorship is intricately tied with authority, and for those of us in medieval studies we divided “experience though noon auctoritee” from the Wife of Bath’s prologue while also attempting to decipher the various meanings of “auctorite” found in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale all the while formulating connections between the two, among innumerable other encounters with the term.

But that was the beginning many years ago, and now I find myself questioning authorship from the margins in terms associated with its physicality – transcribing, collating, describing, and editing – asking myself how these processes fit into the existing parameters of authorship. I have personally come to the conclusion that they usurp authority and consequently authorship by virtue of creating meaning within their respective confines. In other words, all of these functions are imbued with the power of creation (or recreation) and challenge the axiomatic understandings of “writing” – or whatever that term entails.

Yesterday evening I received a very exciting email being invited to present at a colloquium at the University of Minnesota on “Power, Kinship, and Gender” where I will be discussing the role of female authors in thirteenth century France. My paper traces the relationship between female scribal activities and the power often wielded through the process of writing, and more importantly editing (specifically within a single manuscript) during a time period when the privilege of magisterium vocis was revoked from women via Gregorian Reforms (should you be in the area, the colloquium will be held April 17th).

While researching and reworking my findings and writing my paper I constantly returned to the same question: what is an author? I am certainly not questioning Chretien de Troyes’s original work on the Arthurian legends, nor am I ascribing the post-vulgate version of this text to any one person, but I find each rendering of the tale a nuanced version of the original, recalling there are over two hundred extant manuscripts within the Lancelot cycle alone. Morseso, each edition tellingly bears an agenda where every hand responsible for its reproduction carries its scribe’s signature far beyond colophons. But what does this mean?

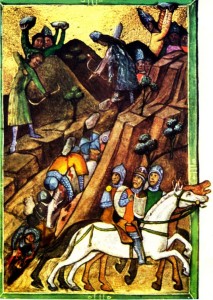

This is where I reach an impasse. While I focus on the single female scribe of Paris, BnF fr. 342, her emendations serve to question authorship, scribal activities, and even gender boundaries. Her ambitions are a cross between all of the above and bring to question my most simple understandings of textuality where I am forced to draw a line between original text and textual scholarship – is she engaging in such scholarship when she consciously edits her primary sources, including illuminations? Further, are the graphics, or illuminations associated with her fair copy of the text inclusive in the analyses of the manuscript? Are the two intertwined within what would be considered a “text?” Is she an author of the images by virtue of guiding the artist via her word choices and specified narrative? How does the manuscript as a whole relate to the evidence presented by her selection and omission of the original text?

I have serval conjectures that I present in my paper, and I admittedly ascribe much power to her scribal activities. But I also invite debate and conversation on the topic where I deliberately leave gaps for interpretation because as much as I navigate through the murky topic of authorship, I don’t have all the answers. My research leads to various conclusions, and I firmly believe she had an agenda. Yet, as she pens her manuscript and edits the story of Lancelot, even as she breaches the boundary between scribe and creator, the question remains: what is an author?

Comments?