A few weeks ago I wrote this post exploring the idea of the female scribe. I won’t reiterate everything, but that post lead to several inquiries into what female writing meant during the Middle Ages. Matthew provided me with an excellent recommendation for a book that I just recently got a chance to finish. My ultimate goal for this project is to look into one of the earliest dated Lancelot manuscripts from 1274 (Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale MS fr. 342) which indicates its author as female. I want to determine to what extent (if any) the story was influenced through having a female scribe. I think this calls for a close comparison between this telling of this story and several others to mark the differences. Honestly I am not entirely sure if that is the best approach, but for now this is the plan. However, before I can draw any conclusions, or even begin work with the primary texts I think it is important to first identify and understand the different ways women interacted with books and writing – which is precisely why Women and Writing c. 1340-1650 was so useful. This collection of pieces got me thinking of what writing represents and the ways it was used, or purposely not used (a point I found very interesting and will get to shortly).

One of the first articles in the book mentions translating – commonly done by women in the early modern period – which leads me to believe it was given to women even earlier than that as it was believed to be a simple (minimal) task where ideas from one language were conveyed in another – essentially another form of direct copying. This struck me as odd since anyone who has translated text will know there is a very fine (if not completely imaginary) line between translating and recreating, where if enough liberties are taken, entirely new ideas can be forged from existing text. Even when attempting fidelity towards the original, words in different languages often vary in connotation. This leads me to believe that it was not the task itself that was thought to be minimal, but rather that the women bid to translate were thought to be too dull to provide any reinterpretations of the original text. Yet I am not exactly convinced of this either since even pure translation is an arduous task, so I am having trouble consolidating that concept with the contradicting idea of woman as slow minded. Further, women were often publicly praised for their excellent translations that were widely circulated among women and men alike. As Gemma Allen notes, translation was but a stepping stone for women towards agency within writing while finding a means for furthering their own ideologies.

Again, this is a concept I can extrapolate into the earlier times of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries where female scribes (much like their male counterparts) participated in a culture of writing that thrived off deriving and creating meaning through textual emendation and manuscript mise en page. It appears that women often operated within this environment by annotating. While this was not direct authorship, as we receive those manuscripts today we cannot ignore the various marginalia left behind by generations of readers who interacted with the text. I would like to believe that it actually alters the way we read the text and begin viewing it through their eyes. And I cannot help but wonder: if they had been the copyist, what manuscript would we have now? In other words, how would they have amended the author’s words?

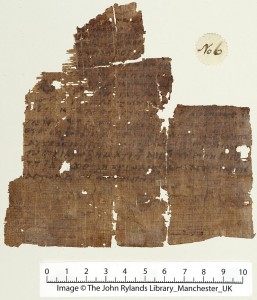

Only two chapters later I came to another point in the book that discussed the place within culture of the commonplace book, attempting to broaden the existing definition, or better yet, consolidating the multiple definitions loosely associated with the genre. However, the point I found most interesting was the “conflation of ‘Scribe’ and ‘Authour'” referring to a poem written by Henry King. While we can all accept that writing and reading are intricately tied, authorship (creation of ideas) and scribal activity (the physical act of reproducing ideas) are not always as tightly wound in our minds. Alright, I am going to apologize in advance, but to flush out my point as best I can I am going to have to bring in Derrida. I know very few people who care for literary theory, so I promise to be quick… but… in between the author’s words and the scribe’s hands there is a gap, or differance. Even when attempting fidelity towards the original words, scribes will inadvertently provide information about themselves and their surroundings: spelling will signal geographic regions; book hand will denote period and sometimes even place; depending on the language of the text, verbs will give away gender (etc.). The gap between the exemplar and manuscript is where meaning begins. It is where information is found. Most importantly, it is the onset of authorship where the text is transcribed/reproduced, with the idea of it being (re)created. With each addition, deletion, or edit, the result is always an addition, as in an additional meaning other than the original. And this is simply looking at the differences between exemplars and manuscripts that were created unintentionally. Now imagine if these gaps were produced purposefully where simple line omissions or changing of words could be used to reshape a story in order to include… well… anything… that the scribe, now author, wanted to.

Returning however, to my purposes here, I want to continue with my findings on the ways women and texts interacted. The next few discussions dealt with epistolary writing, long known to be a female endeavor. The letter however, is not solely a female activity as men have been using letter writing in the public and private spheres for just as long. Yet what I found interesting was not the ways in which women entered the public spheres with their letters such as was the case of Lady Rich who addressed Elizabeth I with fruitless results, but rather another instance where letter writing remained private. The particular practice mentioned in the book concerned a mother, Joan Thynne, and letters to her son for which she employed a scribe. While the reasoning behind her choice to use a scribe for private letters to her son were nuanced to this particular case and take into account the strained relationship they shared, it was the activity in general that I thought was interesting. It was not uncommon during the early modern period (and even earlier) for literate women to use scribes when writing personal letters. I looked into Joan’s background a bit and while she was known for her prolific letter writing, most research that has been conducted on her studies the letters she wrote to her sister and her daughter in law, offering glimpses into the various relationships she had with those related to her.

Hiring a scribe didn’t always have to do with hiring someone who could do something that the person could not – many times professionals were (and still are) hired despite a person’s ability to complete a task. Scribes offered services like many other professionals, and the ability to hire one could be construed as a status symbol. However, I also see it as a means of using something created professionally in order to establish credibility, or even more simply to produce a work that is better assembled or more aesthetically pleasing than would be possible by a layman. Similarly, just like it was a common trope for women to apologize for their handwriting (regardless of whether it was legible/neat or not), it was also common for them to feel their writing was somehow inferior, or worthy of less regard. However, by packaging their words differently, as in with the use of a scribe, their letters would in a sense carry more weight. In other words, the female amateur voice would be translated into a professionally polished one.

In short, the refusal to author a letter, despite the ability to do so, was a rejection of self-conscious feelings. Coincidentally the article on Joan Thynne that produced these ideas for me was also the last piece in the book and got my mind circling back to the relationship between women and writing, or the implications of women as scribes. These two figures are not mutually exclusive, and when consolidating the image of female and scribe a third, rather ambiguous figure emerges. Did the female scribe gain confidence within her double role? As a scribe often working anonymously she could present her words in a genderless domain and with the same authority than a male voice would sustain.

Then, did she understand her power to manipulate text through copying? Or did her insecurities get portrayed within her writing?

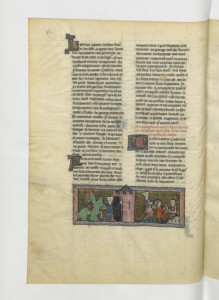

Also, what impact (if any) did the role of scribe have on her identity as a female? Looking specifically at the Lancelot scribe, little is known about her which makes it very difficult to discern how she interacted with her text, or what factors in her life could have impressed upon her. Also, very little is known about the manuscript. It is not fully digitized (which will obviously pose quite a few problems for my own research later on), and from what I have found, the manuscript is most revered for its 92 elaborate illuminations, not it’s text (which to my knowledge has not been transcribed either).

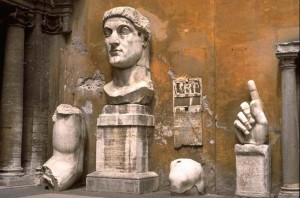

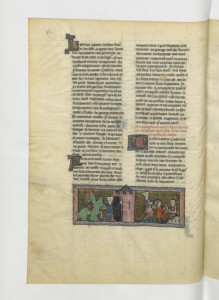

BnF MS. fr. 342 f. 102v – an example of one of the colorful images that spans across two columns. The images are interspersed throughout the text illustrating the various scenes as they are described in words. This is the representation of the tournament in which Lancelot mistakenly takes part in Queste del Saint Graal.

Here is a full page- f. 39v – The portrait of Agloval finding his mother is depicted at the bottom.

This same technique of portraying miniatures across columns was also prevalent in another Lancelot manuscript produced in 1280 by Walterus de Kayo, and coincidentally in the same town as the manuscript I am interested in (which I will discuss in a bit). The town is not large and the time difference between manuscripts is not very big (6 years), so there must be a connection between them. I researched Walter to try to find out how he may be connected to the female scribe, but all I gathered was that his name roughly translates to Walter of the Warriors. I am going to have to leave this alone for now.

Obviously a lot more digging is going to have to go into culling out any information about this manuscript. And I realize I may not find anything specific about that Lancelot female scribe, however, I might be able to piece together some generalizations about females and writing in a broader sense should I be able to pursue this further.

In the meantime, I found another interesting piece that could perhaps be applied in a more universal sense to women of the time period. First, from what little I could find out about the Lancelot female scribe (from this amazing online Lancelot project resource), it appears the manuscript may have been produced in Douai. Although the town is now in what is considered northern France, that territory was not always under French rule. During the Middle Ages it appears the largest construction in the city was the church of Notre Dame (not to be confused with the much larger cathedral that is nowhere near here) that was built in 1175.

These are some photographs I found of it as it looks now (it has been rebuilt several times since the 13th century and the original building was far smaller). For even more lovely pictures of church, go here:

Anyway, this digression lead me to poke around the history of Douai, noticing that aside from the church, nothing else was really happening in the city during that time period, and according to historians like Uge, there appears to be almost no documentation, leaving the history of the area to become quite a mystery. Records didn’t really appear about the town until almost two hundred and fifty years later when it flourished with various enterprises, including a lucrative textile business. So, while this is complete conjecture, I have a hunch the Lancelot scribe may have been a nun, or closely related to the church that the entire town seemed to center around. However, since the church has now burned down on several occasions and has been continuously rebuilt, I don’t know if it had a scriptorium around the late 13th century(even though one would not absolutely be needed for the production of a manuscript). Also, I would be interested to know when and from where the BnF procured the manuscript (meaning, it obviously didn’t get damaged or destroyed by the various calamities the church went through, so if it’s travel history does not match the different known events of the church, then it may not have been produced there).

To wrap this up, my findings on the town of Douai along with my speculation that the Lancelot scribe could have been a nun could lead to an investigation into what being a nun at the time, and in that region meant. This is a rather large leap that will require quite a bit more research, but in looking at what it meant to be a woman in the Middle Ages I found a reference to Aethelberht’s laws. I won’t go into too much detail here since this post is already running far longer than I intended, but I promise another one soon which will better address my connection between the significance of these laws, being a nun, and the ramifications of partaking in scribal endeavors. However, briefly, the laws are concerned with defining a woman’s worth, and notably “maegpbot sy swa friges mannes” (a maiden’s worth is equal to that of a man), and a “friwif” is, as her name indicates, independent for one reason or another. A nun would fall under either of these conditions, either a maiden from the start, or released from relations with men at a later time. In the hierarchy of worth, according to Aethelberht, these would be the highest ranked women. Basically I want to explore how (or if) perceiving themselves according to this value system would imbue these women with the necessary assurance to commit words to paper (or parchment, or vellum) in a mode uncharacteristic of women in different stations or spheres.

While I seem to be no closer to working with my primary texts or finding any definite answers, I have to say all the research that has gone into the female scribe project has been quite some fun, and I look forward to continuing along.

Sources:

Busby, Keith, ed. Les Manuscrits de Chretien de Troyes. Vol. 1

Frappier, Jean. La mort le roi Artu: roman du XIIIe siecle.

Lacy, Norris J. The Fortunes of King Arthur.

Lawrence-Mathers, Anne and Phillipa Hardman, eds. Women and Writing c. 1340-1650.

Littleton, Scott. From Scinthya to Camelot: A Radical Reassessment of the Legends of King Arthur.

Pasternak, Carol Braun. “Negotiating Gender in Anglo-Saxon England.”

Uge, Karine. Creating the Monastic Past in Medieval Flanders.

van Houts, Elizabeth. “Women and the Writing of history in the early Middle Ages: the case of Abbess Matilda of Essen and Aethelweard.”

Williams, John. Women’s Epistolary Utterance: A study of the letters of Joan and Maria Thynne, 1575-1611.