(Chaucer’s pilgrims of the Canterbury Tales as depicted by William Blake)

I am probably not terribly off when stating that every medievalist has read the Canterbury Tales, and most can recite large parts, especially the beginning of the General Prologue, from memory. Lines 12-18 read:

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

And specially from every shires ende

Of engelond to caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

[Then folk long to go on pilgrimages,

And pilgrims to seek foreign shores,

To distant shrines, known in sundry lands,

And specially from every shire’s end

Of England to Canterbury they went,

To seek the holy blessed martyr,

Who helped them when they were sick.]

Here, the holy blessed martyr refers to Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury in the mid twelfth century who indeed was the influence of multiple pilgrimages to Canterbury Cathedral, and most notably the visit of Henry II that will become the focus of this post.

This may well be one of the better known incidents of history (and from what I have been told, all students in England study the conflict between Becket and Henry fairly early on), but from my own experiences few medievalists focus on Becket directly where I am, and I am not entirely sure the history between him and Henry II, who originally appointed him to the role of Archbishop of Canterbury, is often looked at these days. The intricacies of their affiliation and the various political ramifications of the post extend well past what I will attempt to do here, but there is one aspect of Becket’s history that I think has helped shape England’s relationship with kingship that I want to look at which, perhaps ironically, he was responsible for posthumously. So, as a reminder of a history each of us have perhaps learned via various means, here is a brief rehashing of an exceptional event and its consequences.

From a historiographic stance, according to four chronicles, most notably that of Edward Grim, Becket’s tie with Henry II weakened shortly after his appointment to Archbishop when he began diverging his policies from that of Henry who became disappointed that his chosen church official was not placating him. Matters become worse over time until Becket outright refused Henry’s ordinances, infuriating the king and provoking a statement that insinuated he wanted the Archbishop permanently removed. This exchange must have taken place at some point around what we would today refer to as Christmas, as only a few days later, December 29th, 1170, Thomas Becket was murdered. Whether Henry gave the command, indirectly stated he wanted the man dead, or was simply venting is unclear – accounts of his exact words vary too much for an indisputable conclusion to be drawn. As an absolutely unrelated side note, and perhaps because I just finished teaching Faust, this very much reminds me of one of the last sections where Faust mutters his wish for the death of Philemon and Baucis only to realize his words were literally understood and the couple had been murdered. Again, little in the way of evidence remains of Henry’s words, but his previous sentiments about kingship, the role of the church, and in regards to Becket himself resonate with the rumors about his alleged instigation and role in Becket’s murder. Yet, like Faust almost seven hundred years later, Henry will demonstrate his remorse. However, unlike Faust, Henry’s demonstration will be extraordinarily public, serving to highlight the importance of public opinion in the maintenance of kingship even during a time thought have been predisposed to dictatorial tendencies.

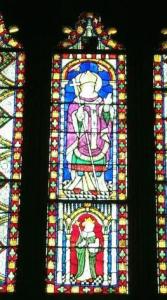

(Stained glass from Canterbury Cathedral – Church official, most likely a bishop, is significantly depicted much larger than the lower pane, the king, demonstrating the true place of power, at least as it was perceived by the church)

Becket may have had substantial influence prior to the fateful night of his murder, but the aftermath marked the church’s place in medieval culture, and where it would remain until Henry VIII eradicated Becket’s shrine while simultaneously gaining complete control over the Church of England, essentially undoing what his predecessor two hundred years before, Henry II had no choice but to do.

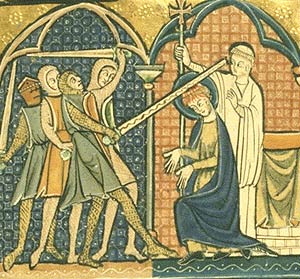

(Thomas Becket’s murder by the four assassins, in the Huth Psalter)

Many more manuscript pictures of Thomas Becket and Henry II can be found here.

Becket’s murder transformed him into a martyr, and more importantly poignantly highlighted the deficiencies in the state. Upheaval ruled England with each year, and after Becket’s canonization by Pope Alexander III, his infamy spread throughout the land and all those who had qualms with Henry II’s rule emerged to voice their displeasure – the vox populi became a formidable weapon to be wielded in the face of tyranny. Henry’s reign was more threatened than perhaps all others before, including Offa, Eathelred, and William Rufus, combined. His meddling in the affairs of the church and the results were indicative of the change in climate – unlike William I and his immediate heirs, intimidation and egregious brutality were no longer enough to subdue the public, and as rioters were well out numbering royals forces, the nation’s very existence was threatened. If the fairly newly forged Anglo-Norman England was to survive, drastic measure needed to be applied.

Henry II went on a pilgrimage to Canterbury in what would probably be considered one of the earliest public relations campaigns rivaled only by his grandfather, Henry I, who went to extraordinary lengths to bridge the gap between the Normans and Anglo-Saxons. Henry II, realizing his error in alienating Becket and his supporters set out to create an example of himself as, on July 12, 1174, he fasted, and then ventured stripped in only woolen clothes and barefoot for three miles to the shrine of Thomas Becket at the Cathedral of Canterbury to ask forgiveness for his sins. He prostrated himself at the shrine, and subjected himself to a public scourging before all of the clergy present where the bishops, abbots and each of the monks of Canterbury flogged him. Afterwards, he lay all day and all night on the cold stones in front of the shrine.

His penance and public humiliation were well calculated at the exact moment they were most needed and almost immediately paid off. Henry secured his throne.

Some images of Canterbury Cathedral:

(The sign on the floor in the above photo reads: The candle burns where the shrine of St. Thomas of Canterbury stood from 1220 to 1538 when it was destroyed by order of King Henry VIII”)

Sources:

Howlett, Richard, Ed. Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I.

Partner, Nancy F. Serious Entertainments: The Writing of History in Twelfth-Century England.

Staunton, Michael. The Lives of Thomas Becket.

Stubbs, William, Ed. Chronica.

Stubbs, William, Ed. The Chronicle of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, by Gervase, the Monk of Canterbury.

Walsh, P.G. and M. J. Kennedy. The History of English Affairs, Book I.

Warren, W.L. Henry II (English Monarchs).

Winston, Richard. Thomas Becket.