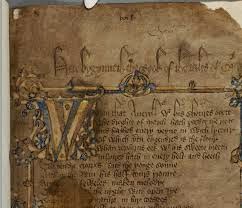

Thus far I have spent the last few sections of this discussing the integrity of Fragments IV and V, attempting to demonstrate their completeness as one unit. As you can tell if you have been reading along, my progress has slowed. The problem is, I am running out of resources. I have digital copies of some manuscripts, and pictures of various parts of others, but the problem with independent research is that I have no access to massive data bases. If I was only doing a literary analysis that would hardly be a problem, but the nature of this project relies heavily on visualization, meaning that until I can get a better idea of the original works, I am a bit stumped. Even within this section I will be focusing more on traditional literary analysis, with fewer references to the manuscripts.

After my argument for combining Fragments IV and V, I will refer to my previous (and brief) mention that several stories within these sections must follow the Wife of Bath, meaning that both Fragments must follow her as units. Further, Fragment III, containing the Wife, must remain intact as is, comprised of the Wife, Friar, and Summoner. As I inquired in the previous section, why? Part of the answer is very simple, and I will address this first.

Immediately preceding the Wife’s Tale the Friar and Summoner break out into an argument that will find it’s way into the prologues of the other two tales within this fragment, serving as the link between all three tales. Several other tales have endlinks or interruptions that introduce another character or form a connection, but here, among all three tales (four if you count the Wife’s Prologue, as I will do), it is always the same characters, binding not just two stories together, but an entire fragment from beginning to end. Yes, as was seen in the Merchant’s, Franklin’s and Squire’s prologues and endlinks, scribal insertions often occurred, but when they did, there were generally brief, lacking depth and hardly adding anything to the stories. This is an argument that does add (albeit not to the stories themselves) to the overarching theme of the tales; commentary among members of the pilgrimage gave the frame narrative of a journey a certain three dimensional quality as opposed to a linear prologue-tale-prologue-tale mechanical organization. It also serves to remind the readers that there were other characters there. Much like the Host acts as an active audience member to the pilgrims’ stories, so too do the commentaries prompt us to reflect on what we have read.

On the topic of scribal insertion/authority, in the few places where the scribes interchanged the names of the pilgrims within endlinks or prologues (Merchant, Squire, Franklin), the disparity between who was being named and their statements made it immediately apparent that something was not right. With a little digging it was generally ascertained where the error occurred, especially when there was an absolute lack of contextual support for a revision of what may have been the original, and which made most sense.

Also, importantly, these three tales have never been separated from each other in any of the manuscripts. While manuscript consensus is not necessarily indicative of an absolute ordering, it does strongly imply that copies of these tales have never been received in a different order and quite possibly as one long piece making it impossible to recopy them in any other way. As scribes shuffled loose stories around, none would amend a continuous portion of text.

Moving away from the physical aspect of the quires containing the tales, I want to focus on the structural similarities within Fragment III, much like I had done with the components within Fragment IV and V. Since the Wife’s Prologue is quite lengthy (even more so than some of the tales), I will treat it as a tale, especially in light of the contextual parallels that are found between it and the three tales in this fragment. What I hope to present at the end of this is an illustration of four quarters that not only complement each other in completing the fragment through structural similarities, but remain in constant conversation, tying all the stories, including the Wife’s Prologue, together.

Unlike the tables I have tried constructing in previous posts, with four pieces it would be impossible, so I will outline the structure step by step.

Wife’s Prologue: WBP Wife’s Tale: WBT Friar’s Tale: FrT Summoner’s Tale: SumT

The first set of similarities is among introductions, and obviously most tales and prologues throughout the Tales have introductions, making this first section appear superfluous. However, I want to draw attention to the endings of each introduction where the similarities between these four segments are strictly characteristic of Fragment III.

WBP: Alisoun introduces herself in her infamous “experience, though noon auctoritee” speech. Before she begins her list of husbands and marital vignettes, she attacks the institution of marriage as it is preached (not practiced), and the traditional conventions associated with it. Marriage, a beautiful concept when taken more loosely, is the subject of her harangue in its strict state that prohibits any joy a woman might have.

WBT: In her tale the Wife introduces the Knight, and immediately tells us of his conundrum, namely that he raped a maiden and is about to have his head lopped off. Interestingly that entire part gets glossed over and instead the Wife narrates a grievance against the imposition of chastity.

FrT: The Friar in his tale introduces his two main characters, the Archdeacon and Summoner. Unlike the Wife’s Prologue, and Tale in which she railed against concepts (as outrageous as they may be), here the Friar directly offends the Summoner to the point where the latter interjects.

SumT: The Summoner retaliates against the Friar and tells a bawdy tale involving the humiliation of friars to where the Friar interjects (which conveniently brings me to my next point).

Once all four tales have had their introductions, before the body of any tale, there is an interruption. Yet unlike the other tales where interruptions halt the tales completely, here the story tellers continue on either on their own or with encouragement from the Host.

WBP: The Pardoner interrupts the Wife’s tirade against the sanctity of marriage. Even though he only does so to praise her words, she advises that he has not heard all she has to tell (and indeed she has about 700 more lines before she even begins her story).

WBT: After she harshly reprimands the Pardoner for interrupting her prologue no one else dares stop Alisoun in her story, however, at one point (as several others have also pointed out in their criticism), she uncharacteristically steps out of the role of narrator. After introducing her Knight in King Arthur’s court she uses the first and second person pronouns for the brief section. This is the only point in the story where this appears, and only continues for a few stanzas. While it is not an interruption per se, and not even very distracting (often not caught on the first read), it is an intrusion into her narrative.

FrT: As the Friar and Summoner are on a retaliatory path, as the Friar introduces his lecherous summoner, the pilgrim Summoner interjects. He does not openly show offense, but if we learned anything from the Miller and Reeve previously, we can already deduce what tale the Summoner will tell. Also, if the Host had not called for “pees” the two may well have gone back and forth over the depiction of summoners.

SumT: Yes, the Summoner begins a tale about a corrupt friar, and the Friar interrupts his tale. Once again the Host calls out for “pees” and the tale resumes.

The third set of structural similarities is concerned with each character’s pursuit. Unlike several other tales that simply tell a story, or convey a moral, here each one is actually in search for something whether tangible or not.

WBP: Alisoun makes it clear that despite having had five husbands at church’s door, she is in search for number six, and uses her marital stories to illustrate what she is and is not looking for in a mate.

WBT: The Knight of this tale is in search for the answer to the question of what women want. In a sense this is almost a direct answer to the Wife’s Prologue; if all of her previous marriages were combined, her ultimate goal, much like the Knight tells the queen, is sovereignty.

FrT: The summoner travels around looking for money and how to obtain it from people.

SumT: The friar goes from home to home, much like the summoner in the previous tale, searching for monetary gain. Even as the means are different (here people give money out of charity and perhaps due to trickery, but for the previous summoner it was out of fear), the end is the same.

Once the tales are told each has an ambiguous conclusion.

WBP: After telling the audience all about her husbands, especially those who were cruel, the Wife claims she has obtained “by maistrie, al the soveraynetee.” However, in the last few lines of her prologue she relates what a “trewe” wife she was to her husband, kinder than any woman from “Denmark to Inde,” which seems a complete negation of her previous sentiments.

WBT: In her tale, practically a parallel to her prologue,the Wife asserts that the Knight was taught a good lesson about the “governance” women hold. And the woman in the story, much like the Wife, chooses to use her power in the end to make the man happy and surrender to his desires as the old crone turns into a beautiful maiden and swears loyalty to the Knight.

FrT: The Friar ends his tale with his summoner being taken off to Hell and a brief reminder that we should not sin lest we also end up there. However, the lesson that is more apparent (especially when regarding the Friar in terms of how he was introduced in the General Prologue, along with keeping in mind Chaucer’s propensity for making unstated commentary) is that there is a difference between verbalized speech and actual meaning. Much like the man with the cart who the devil would not haul away because he did not mean it when he sent his cart to Hell, the old woman does mean it when she sends the summoner to Hell, but under this same premise we are invited to analyze the sincerity of the Friar’s words as he preaches virtue in the ending lines. As the Friar endeavored to defame the Summoner with his tale, he managed to draw attention to himself.

SumT: The Summoner’s tale is a bit more subtle in the secondary meaning. While the Friar is obviously attacked as a charlatan taking advantage of a grieving family, the Summoner finishes by praising Jankin, a churl, for his wit and rhetoric comparable to the likes of “Euclide or Ptholomee,” and much like the Friar had done at the end of his tale, the Summoner draws attention to himself; he not only applauds those traits that the Friar feels belong to him, but puts them onto a man who’s other attributes (that are far more disagreeable) parallel the Summoner instead.

When looking at the stories piece by piece their structures overshadow their disparity in genre and superficial style. Fragment III, unlike any other fragment is a mini tapestry that weaves the Wife, Friar and Summoner in and out on too many occasions to argue against their coherence. So while on the surface it is difficult to see why these characters might be so right together considering they come from different social classes, tell tales of different genres, and the Wife’s Prologue stands out more so than the others, they remain intact on the page because they were clearly written together. As for why they were written together, there are many theories, and I have one myself, but in truth, only Chaucer knows.

So far I have managed to cover four out of the ten fragments. Some, like Fragment I, don’t necessarily warrant explication in the sense of ordering as I can’t imagine anyone disputes the Tales start with the General Prologue. The same can be said about Fragment X, except there is some debate as to what comprises that fragment along with the Retraction. In the next part of this I want to look at the Man of Law’s relationship to his own fragment (II) along with his influence on Fragment III, and I want to explore how his tale has moved throughout the various manuscripts.