Every time Sean comes home from grad school for a bit we have coffee and play chess. Last time was no exception, and somehow the conversation rolled around to the history of chess, specifically to the way it was played in the Middle Ages, and how the pieces differed (not just in appearance, but also movement).

Chess originated in India and through a series of moves ended up on Europe where it was widely played during the medieval period, resulting in the version of the game we have today.

First, chess is comprised of only six distinct pieces: pawns, rooks, knights, bishops, the queen, and the king. However, these pieces were for the most part created during the Middle Ages. Essentially the game was adapted from the east, but westernized to fit the purposes of those in the west – the new names and roles the pieces played were made to make sense to Europeans. One fact I found personally interesting was that there was no queen in the original game, but rather a male advisor figure was situated next to the king, evincing the important role queens played in western culture a thousand years ago. While the queen is the only female piece on the board, it is important to note she holds the most power and is allotted the most freedom of movement (with a caveat I will discuss shortly).

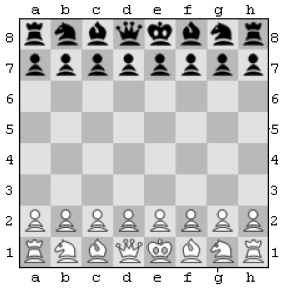

For those unfamiliar with the game, here is a brief outline what the pieces symbolize.

Looking at just the white pieces at the bottom, A2 thru H2 are all pawns. Symbolically the pawns were thought to resemble the serfs or commoners of the land. However, a more accurate description of them I found was of the infantry. The reasoning behind this altered analysis of the pieces was due to the significance of serfs versus infantrymen. The former were thought to have value attached to the labor they conducted, while the latter were often no more than fodder during war. While the pawns in chess can be invaluable in certain situations they are often sacrificed in order to clear the board and are the first to be captured as they advance the lines (aside from the knights, no other pieces can move until the pawns are moved out of the way). The pawns move forward only one square at a time, and during the early Middle Ages this was always the case. They “take” pieces diagonally. In the fifteenth century, perhaps to move the game along faster, each pawn could move two spaces for their first move if the player wished them to and this rule remains today. Another invention for the game that came during this same time which concerned the pawns was the en passant that allowed pawns to capture pieces “as they passed.”

The rooks are the “castle” looking pieces at the corners of the board. They represented quite literary what their name implies – castles, home, or refuge. Much likes castles or fortresses, strategically they function best together. They can move vertically or horizontally across the board just like castles or fortresses had command over vast amounts of land. During the Middle Ages the castling move was invented which serves two purposes: it shields the king into a corner to be better defended, and allows the castles more freedom of movement, brining them closer together.

The knights are pretty self explanatory in terms of historic meaning. In the game, portrayed as horses they are the only piece that can jump over other pieces as they move in an L shape (two squares up and one to the side). Sean briefly mentioned that the knight at one point in history moved in a different form, but so far I have not been able to find anything on that.

Bishops were during the original game portrayed by elephants, thought to be dependable animals, and the piece could only move one square at a time. However, considering the role of the bishop as advisor, on the western chess board he sits closest to the royal couple. He moves unlimited spaces diagonally across his base color (one bishop always sits on white and the other on black). Between the two of them, they can influence a large amount of the board.

The queen is now one of the strongest pieces on the board being able to move in the same way as every other piece except the knight. However, this was not always the case. While in the original version of the game she didn’t even exist, in later versions shortly after her introduction her movements were limited (late fifteenth century).

The king is the piece around which the entire game centers. The objective is the render the king helpless by placing him in direct peril (check) without the ability of aide (mate). The king can move one square at a time in any direction. When the majority of the more powerful pieces are removed from the board, the king by himself can do little more than hop away one square at a time as the opposing pieces are closing in on him. It is really quite a pathetic spectacle, but I think it speaks volumes of the distinction between perceived and actual power (and personally each time this happens in a game I can’t help but recall Shakespeare’s Richard II).

One of the earliest sources of chess play in medieval Europe came from Versus de scachis, a latin poem that is thought to have been written before 1000. It exists in two copies, MS Einsidlensis 365 and MS Einsidlensis 309. The 98 line poem describe chess, it’s rules, and contains some basic strategies.

Then, in 1283, Alfonso X of Castile commissioned Libros de los juegos, a book dedicated to various medieval games and their practices. This too discusses strategies and rules of the game.

(Biblioteca Monasterio del Escorial – depicted: Alfonso discussing a chess problem with other players).

(same MS)

In 1474 William Caxton published The Game and Playe of the Chesse, a book which has very little to do with the actual game of chess. It is in fact a translation of Jacobus de Cessolis’ Liber de moribus hominum et officiis nobilium ac popularium super ludo scachorum (The Book of the Morals of Men and the Duties of Nobles and Commoners, on the Game of Chess). Yet, while this book in either Latin or English has nothing to do with the game, it serves to demonstrate the influence society had on the game, and vice versa. Further, I think it shows why this game was so important among the nobility, who were, for political reasons constantly playing metaphorical chess. Hence the pieces that were switched out from the original version to reflect medieval concerns and relationship among pieces (members of court). While chess, strategy, and politics are all loosely tied in our modern minds and we have all heard the metaphors, during the Middle Ages these same connections were being forged, and I love the idea of chess, a newly acquired game slowly seeping into the world of stratagem outside the corners of the board.

By the fourteenth and fifteenth century, chess had the same notoriety it has today and references to the game were hardly novel. One last example is from Chaucer’s Book of the Duchess in the Knight’s complaint about Fortune:

“For fals Fortune hath pleyd a game

Atte ches with me, allas the while.

The trayteresse fals and ful of gyle,

That al benoteth, and nothing halt,

She goth upright and yet she halt,

That baggeth foule nad loketh faire,

The dispitouse debonaire,

That skorneth many a creature!”

Here chess is not a game of strategy as a game of deceit. The Knight does not understand the ways in which Fortune works so he may only apply them in terms of his own earthly understanding and compares Fortune’s bidding to a game of chess, where Fortune wins through foul guile that scorns his human mind – she does not cheat, but moves pieces in ways he cannot perceive. He cannot comprehend that he is a part of a larger scheme and Fortune’s actions do not necessarily focus on him. Further, the Dreamer has difficulty looking beyond the chess metaphor to grasp the Knight’s loss, consoling him not on White’s death, but reminding him that he should not weep over a game. Tellingly, and unwittingly, the Dreamer actually pinpoints the exact shortcoming in comprehension on both their parts – life is little more than a game where everyone loses in the end.

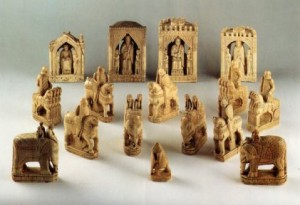

While examples of chess in literature at this point abound, I wanted to end with showing you some lovely medieval chess sets.

(The Original Chessmen – National Museums Scotland)

Above are the Isle of Lewis Chessmen which were created at some point between 1150 and 1200. Here is more information on them if you wish.

Here is the Charlemagne Set (despite that Charlemagne apparently didn’t play chess). These are housed in the BnF, and are made of ivory (which I will refrain from commenting on).

As you can see artists of the Middle Ages took great pride in producing their chess sets, crafting them into the actual pieces they were meant to represent very much unlike the little plastic generic pieces we have today. This is not to say such fine sets do not exist today, but the idea of a hand crafted unique set, not mass produced is rare.

Which brings me to my last point, of how the pieces were represented in earlier times. I thought there would be a difference. But, while the sets depicted above (among others) are exquisite, I have found that not much has really changed in terms of their appearance. As the scope of chess playing has broadened and the game has become public fair the pieces have taken on a more generic shape that could be easily disseminated to the masses. However, these rare sets do exist. I have seen collector shops that sell beautiful chess sets comparable to those seen in museums (despite having been recently created). In short, the appearance of the pieces has not dramatically changed. At least not so much so that these pieces would be indistinguishable from each other.

So while chess has come a long way, the various changes it has undergone have not altered the scope of the game, and it continues (from the 6th century when it was first created in India) to act as a cerebral exercise in strategy on and off the game board.

Sources:

Adams, Jenny. Power Play: The Literature and Politics of Chess in the Late Middle Ages.

Davidson, Henry. A Short History of Chess.

Dwayne E. Carpenter, “Fickle Fortune: Gambling in Medieval Spain,”

Murray, Harold James. A History of Chess.

Proctor, Robert. An Index to the Early Printed Books in the British Museum.