This coming year at Kalamazoo I will be giving a paper on Lydgate. It is still very early, and I am not entirely sure how I want to frame my paper, but I figured the best approach is to first brush up on my Lydgate scholarship, and reacquaint myself with his works that I have not visited in a while.

I am not sure if any of what I blog about over the next few weeks will ever even make it into my paper, but it will be a fun exercise anyway. I am going to start by looking at A Complaynt of a Loveres Lyfe. However, I won’t attempt all 85 stanzas in one post – I will break it up over a series.

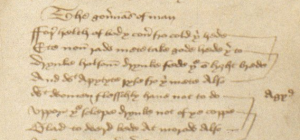

The work is found in nine extant manuscripts, and I will be using Bodley MS. Fairfax 16 as my base text (the infamous manuscript that spends nearly two folios rebuffing the poet, in a long line of others who have felt the need to mercilessly discredit his poetry). Despite some variations this manuscript is the least corrupt. The poem is considered to be one of Lydgate’s earlier poems, from 1398-1412.

The work is typically Lydgatean, especially in his formative years that closely mimicked Chaucerian works but without the later Lydgatean voice that contained a measured seriousness and propensity for over-explanation, all of which allowed him a great range of genres and tones to work with, turning him from a Chaucerian imitator to a nuanced poet in his own right. Although, his indebtedness to Chaucer remained visible to readers familiar with both, along with his own accounts of his inspiration that was clearly drawn from Chaucer’s works.

The Complaynt immediately signals its ties to the Complaint unto Pity, Troilus, and perhaps most obviously, the Book of the Duchess, especially considering the The Complaynt of the a Loveres Lyfe later becomes referred to as The Complaint of the Black Knight – a figure drawn directly from Duchess. The process of loving, as described by the lover in the poem bears a close resemblance to the Roman, especially Amors’s speech to L’Amant. The latter part of the Roman, namely Jean de Meun’s contributions, bear little implications for Lydgate – he does not appear interested in the more complicated conjectures about love. Further, at no point does he attempt to alter the lover’s state of mind or to pacify his lament, probably because despite the anguish and torment the knight is experiencing, there is no moral conflict present in the story, and thus nothing exists to modify or reprimand.

Yet, it is during the knight’s lament, in which he outlines his grief and heartache where Lydgate demonstrates his early career compulsions for rhetorical exercises, over-explanation, and over-drawn examples. This is most interesting when taking into account that while he does not attempt to remedy these laments, but simply allows them to exist as they are, he encapsulates them by a succinct, beautifully and well written beginning and ending to the poem comprised by the descriptio loci and the closing prayer to Venus.

Here is the first part of the poem with some brief descriptions and analyses for each stanza. For more detailed scholarship, I have included a list of sources.

In May when Flora, the fressh lusty quene,

The soyle hath clad in grene, rede, and white,

And Phebus gan to shede his stremes shene

Amyd the Bole wyth al the bemes bryght,

And Lucifer, to chace awey the nyght,

Agen the morowe our orysont hath take

To byd lovers out of her slepe awake,

If flowers are engendered by April’s sweet showers, by May they are in full bloom. Clearly this is an echo from the “when” “then” statements of the General Prologue. In another borrowing from Chaucer, Lydgate’s description of Flora as a “fressh lusty quene” is the same as Chaucer created for Dido in the Legend of Good Women, which also serves to taint the reader’s perception of Flora as she becomes intricately tied to Dido’s history. However, Lydgate liked his Flora imagery, and redeveloped it within a more mature poetic state nearly a decade later in the Prologue to the Siege of Thebes: “Whan that Flora the noble myghty quene / The soyle hath clad in newe tendre grene…” (lines 13-14).

However, beginning a lover’s lament in May also keeps with convention. May is associated with rejuvenation, the casting off of winter, and brings with it a general celebratory mood. Thus juxtaposing the ways in which May is typically conceived with a lover’s melancholy draws attention to the lament as something that should not be.

The poem is set up in such a way in which May is the harbinger of all that is initially expected, and placed within a natural world ripe and fertile with possibility. Phebus, the sun, burns brightly, as Lucifer, the morning star, chases away the night across the sky in order to shepherd in the next day and allow lovers to awaken from their sleep.

These lines echo a cornucopia of previous works. In Troilus, “Whan Phebus doth his bryghte bemes sprede / Right in the white Bole, it so bitidde” (Book 2, 54-55). In De Consolatione Philosophiae where we learn the day and evening star are one and the same, “and aftir that Lucifer, the day-starre, hath chased away the dirke nyght.” In the Romaunt “A slowe sonne! shewe thin emprise! / Sped thee to sprede thy beemys bright, / And chace the derknesse of the nyght….” (lines 2636-2638).

The beginning stanza of this poem clearly works to situate it within the realm of its predecessors as it carves out a piece of the mythology that is embroidered within the text of the others, for itself.

And hertys hevy for to recomforte

From dreryhed of hevy nyghtis sorowe,

Nature bad hem ryse and disporte

Ageyn the goodly, glad, grey morowe;

And Hope also, with Seint John to borowe,

Bad in dispite of Daunger and Dispeyre

For to take the holsome, lusty eyre.

This stanza takes the reader directly into the Romaunt, with references to personified Hope and Danger in conjunction with the lover. Despite Danger and Despair, Nature and Hope invite lovers to step outside and ease their sorrow with some fresh air. Of course this brings to mind the lover’s quest for the rosebud in the Romaunt, and draws a parallel of how these allegorical figures will function in this poem.

While the phrase “with Seint John to borowe,” is a direct reference to Chaucer who uses it in the Complaint of Mars, and at least twice in the Canterbury Tales, it is also a common sentiment to convey while wishing someone good luck in an endeavor. Thus Hope, with the luck endowed by St. John, will, despite Danger and Despair, bade the lovers to partake in some wholesome lusty air.

And wyth a sygh I gan for to abreyde

Out of my slombre and sodenly out stert,

As he, alas, that nygh for sorowe deyde –

My sekenes sat ay so nygh myn hert.

But for to fynde socour of my smert,

Or attelest summe relesse of my peyn

That me so sore halt in every veyn,

In an inversion of the traditional dream vision poems, the Lydgatean world is awakening. As the narrator awakens full of heartache, the third line is a direct reference to Troilus who, like the narrator, “that neight for sorowe deyde” (Book 4 line 432). He wishes to find a solace for the lovesickness that is clearly effecting him – a malady that in the Middle Ages was a serious matter which could transcend metaphorical heartache into physical ailments and even eventually lead to death. He apparently has only enough strength to rouse himself from slumber and take Nature and Hope up on the offer for a breath of fresh air.

I rose anon and thoght I wolde goon

Unto the wode to her the briddes sing,

When that the mysty vapour was agoon,

And clere and feyre was the morownyng.

The dewe also, lyk sylver in shynyng

Upon the leves as eny baume suete,

Til firy Tytan with hys persaunt hete

Much like the narrator of the Romaunt dreams he awakens in May and goes on a sojourn to a more idyllic location, here the narrator does awaken in May and goes into the woods to hear birds singing. Lydgate again keeps with convention and relies on the locus amoenus to guide the plot which requires the lover to enter a idealized location surrounded by nature and providing comfort for lovesickness and melancholy. The place is typically a forest, alcove, or paradisal garden.

The description is an echo of the Knight’s Tale in which “fiery phebus riseth up so bright / That al the orient laugheth of the light, / And with his stremes dryeth in the greves / The silver dropes hangynge on the leves” (line 1493-1496). Tytan and Phebus may be interchanged for a similar effect that ends in silver dew drops on leaves being dried by bright rays of “persaunt” (piercing) sun. I love this adjective that comes directly from the French in the original Roman, here denoting a piercing and pure heat, unlike anything experienced before.

Had dried up the lusty lycour nyw

Upon the herbes in the grene mede,

And that the floures of mony dyvers hywe

Upon her stalkes gunne for to sprede

And for to splay out her leves on brede

Ageyn the sunne, golde-borned in hys spere,

That doun to hem cast hys bemes clere.

This is a straightforward stanza that describes the effects of the hot sun upon the leaves, drying them with his “golde-borned” or in Chaucerian terms, burned gold beams (CT 1247 in regards to Phoebus). This is also the part of the poem that can be considered over-explanatory, drawing out the description of the sun’s rays perhaps more than needed. However, I have to personally interject and comment on the beauty of these lines that narrate such a simple event to the core minutia of its being. It halts the movement of the poem and hyper-focuses on an event otherwise overlooked, not just in literature, but in everyday life. How often have you stopped to look at dew evaporating from herbs in a garden at the exact moment the sun is rising and makings its way across the sky to the topmost point when the leaves may be proclaimed dry? Probably never, and neither have I, but these lines recreate this inconsequential, yet delicate moment for us to vicariously enjoy through the eyes of the narrator, even if never in our own gardens. So, while others may think these types of stanzas unnecessary, and unendingly verbose, there is much to be said for a man who can translate these negligible and seemingly trivial acts into elegant poetry.

And by a ryver forth I gan costey,

Of water clere as berel or cristal,

Til at the last I founde a lytil wey

Touarde a parke enclosed with a wal

In compas rounde; and, by a gate smal,

Hoso that wolde frely myght goon

Into this parke walled with grene stoon.

The narrator enters the garden and begins going towards the river reminiscent of the Romaunt in which the narrator walks “thorough the mede, / Dounward ay in my pleiyng, / The river syde costeiyng” (lines 133-135). However, this is not the lake of Narcissus, or any other mythological creature. This garden may exist within the trope of locus amoenus but it is restorative and wholesome, similar to the effects of sleep upon the dreamer in Duchess, but nevertheless unlike anything before. Even as there are hints of previous compositions, and Lydgate borrows imagery, in this case the concepts are truly his own.

The last line of this stanza recalls “the park walled with grene stone” in Chaucer’s Parlement (line 122), and many critics believe it is a reference to the abundance of the park, laden with gems such as emerald or jasper. This is especially the case considering the other references to green stones within both Chaucer and Lydage (De Consolatione, and Pur le Roi, respectively), in which the imagery is that of abundance, in line with the luxurious garden the narrators within these stories, including A Complaynt, find themselves. However, I would like to offer another reading in which the park walled with green stone is simply an elaborate allusion to stone walls overflowing with moss and natural verdant overhanging plants. The verbiage might be there, but this is not the opulent garden of the Romaunt, but rather, as we shall shortly find, a self reflexive haven for the narrator to reach his own insights and nurse his wounds. The Lydgatean narrator does not attempt rehabilitating the lover solely because by virtue of his locale, and his abilities at reason, he will accomplish the task himself.

I think this is a good stopping place for this segment, and I will continue forth, posting the poem piecemeal, until I have completed the entirety of the work. As usual, any suggesting or insights are most welcome.

Sources:

Krausser, E. “The Complaint of the Black Knight.”

MacCracken, Henry Noble, ed. The Complaint of the Black Knight. In The Minor Poems of John Lydgate.

Mortimer, Nigel. John Lydgate’s Fall of Princes: Narrative Tragedy in its Literary and Political Contexts.

Norton-Smith, John, ed. A Complaynt of a Loveres Lyfe. In John Lydgate, Poems.

Skeat, Walter W., ed. The Complaint of the Black Knight. In Chaucerian and Other Pieces.