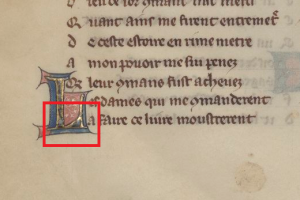

While continuing my work on Paris, BnF fr. MS 342 I came back to this scene:

(folio 52r)

It is a depiction of the daughter of King Pelles laying in bed at Corbenic. For those of you unfamiliar with her role in Arthurian legend, her and her father act to beguile Lancelot into mistaking her for Guinevere, afterwards presenting him with their son, Galaad. She has since been read in numerous ways ranging from temptress and witch to a victim of her circumstances and puppet to the men surrounding her. This particular manuscript takes a distinct stance that firmly positions her on the most bottom rungs of morality. Of the various artistic options available for this folio, she is here shown in bed, representing the part for which she is best remembered. Yet, this is also one of the most prominent associations past and present audiences have made when confronted with the representation of women in bed.

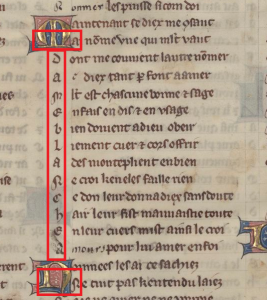

Roughly a little over a decade after the above manuscript, Paris, Bibliotheque de l’Arsenal, ms. 3142 was created, and on the first folio is the image of the woman who commissioned it, Marie de Brabant, Queen of France. She too is in bed.

However, here the bed chamber, an intimate space, is divorced from the physicality implied above. The bedroom, a private and protected quarter, is generally juxtaposed with obscenity as either sanctioned or unsanctioned carnality transpires, or the sick are healing with a faint hint towards the soil paired with, and the cause of, illness, and even in images of giving birth there lies a subtle undertone of the uncleanliness involved in the act. Yet with this iconography of the queen’s bedchamber I argue for a revisualization of the sacred space, unadulterated by those things concerning the body.

Marie de Brabant is surrounded by loved ones, close friends and relatives, along with her favorite trouver, in a different kind of intimate scene that merges the private and public. Her robes, bearing the heraldic symbols of her lineage by birth and through marriage permeate the bedchamber and eradicate any feelings of unease of trespassing. Unlike the daughter of King Pelles, her bedroom scene will cast her in remembrance as the woman who reinvented courtly habits, and through her patronage redefined acceptable tropes within secular art.

About a hundred years later the idea of the queen’s bedchamber as a space for artistic endeavors continued and thrived. Christine de Pizan notably presented her work to Queen Isabeau in her bedroom as demonstrated in another manuscript commissioned by women, for women.

(British Library, MS. Harley 4431 f. 3r).

The ladies in waiting surrounding the queen reflect a fashion that would take hold in courts across Europe as the bedchamber became a means for queens to hold their own court and their majestic beds served as their thrones. This intimate space would be theirs to assert themselves and have free reign to choose those who they invite.

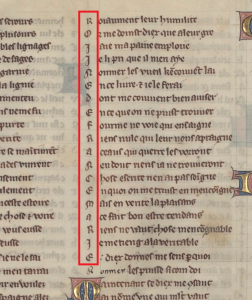

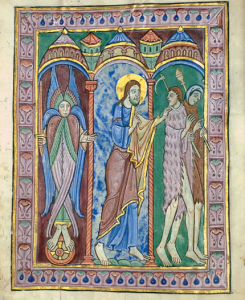

Nevertheless, this is not meant to argue that the bed lost its common connotation (far from it), as can be seen in an early fourteenth century manuscript, also from the Lancelot cycle, depicting King Mordrain and his Queen, Giseult, in bed:

(British Library, Royal MS 14 E III, f. 32r)

However, beginning in the latter half of the thirteenth century such associations were beginning to undergo an ideological shift. This post’s intentionally provocative title calls attention to the disparity between common conceptualizations of the bed chamber and another way of regarding the activities associated with this venue. Returning to the first depiction from Paris, BnF fr. MS 342, considering the overall tone of the manuscript – a lesson on morality disguised as a romance – I cannot help but see the illustration as a deliberate attempt at drawing the distinction between those scenes we want to see, and those that elicit embarrassment from the audience. Further, another disparity emerges as both kinds of portraits operate in line with voyeurism, but their composure distinguishes between the appropriate reactions for each.

The daughter of King Pelles lays on her bed, much like Marie de Brabant, but not poised and self assured. She is buried under a blanket like a body too grotesque to expose in a pose not unlike those that adorn tombs. Despite that “la fille le roi pelles vint a la cort le roi artu se li fist on molt grant feste,” all the fanfare of her arrival to court is undone as Lancelot “ne [sa] daigne seulment nes regarder” [would not even deign look at [her]]. She is unwanted, and her isolation is pictorially made abundantly clear.

Note Queen Giseult’s pose in the last image above who, despite the nature of her encounter, regally bears her crown, and her body does not embody shame, guilt, or necessitate suppression under the covers. Neither she nor the daughter of King Pelles are holding court upon their beds, but carnality obviously carries a different implication for each.

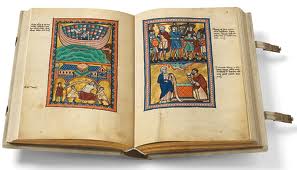

Arguably the daughter of King Pelles’s representation is in line with another from the Orme Bonum “adulterium” scene in the middle of the fourteenth century manuscript British Library, Royal MS 6 E VI:

(f. 61r)

Nevertheless, there is certainly no paucity of manuscript portraits showing people in beds, and while a queen’s bed, fluctuating in meaning, takes center stage for diverse reasons across genres, it appears the daughter of King Pelles’s bed functions within a specific strand of this tradition and consequently serves to draw attention to itself as another instance of uncondoned bedside behavior. The creator of this manuscript had a specific agenda when carrying out the text and accompanying illustrations, and with each nuanced unraveling of the images a broader tapestry of intention can be woven.

As for those of you now asking “what about Guinevere?” I assure you, she has not been forgotten, at least not within the context of my larger project.