Children’s literature, and more importantly for my purposes, the academic study of such literature, has gained significant prominence over the last ten years. Perhaps before I go further I should offer the disclaimer that I am hardly an authority on the genre, and have very limited experience with it outside of having read it to my own children, having had it read to me as a young child, and a brief summer course in Child Lit I took while obtaining my MA. Consequently, it was the course on Child Lit that demonstrated the full range of topics available for academic discussion – I had not until then ever considered Child Lit as anything more than entertainment for children.

I was fascinated, and while I admittedly have not spent large amounts of time on the topic, I ended up outlining the historic/psychological/socio-cultural implications of childhood extending from the Middle Ages into modern times. Perhaps I will turn all my findings into a paper one day. Yet at the moment they are rather scattered, so please bear with me.

In the meantime, I argued that children’s books, if traced through time, could be used as reflections of the way society viewed children at any given point, and the interrelation between these views on children and the messages adults provided for children within literature. In other words, the values outlined within the pages of Children’s Literature speak to the ways in which children were perceived and tell us today the roles children played through history.

My research began with Philippe Aries since no searches for “child” or “childhood” in almost any database will yield less than at least five references to his work. I also used Nicholas Orme who counters Aries’ argument almost to a point of literary attack. After perusing several more authors (sources below), I formed some of my own observations of how children and subsequently childhood historically progressed through the mirror of society, the children’s book.

There appears to be a disproportionate amount of research that believes Aries argued children didn’t exist. I am startled by this egregious misrepresentation of his findings, and even more so for the relative ease with which it has made its way through the grapevines of academia, mutating into a distorted outline of findings on childhood over several hundred years. In reality, he only postulated that it wasn’t until the mid seventeenth century that children, and by extension childhood, were seen as they are now. While he may have overstepped in his analysis when stating that children did not at one point in history receive love from their parents (a point he later counters), his overall argument relied on the treatment of children, and not the emotional implications of having them. Without actual proof to rely upon (and fodder for future research, although I am fairly certain Margery Kempe’s Book II would serve my purposes), I cannot fathom that in the Middle Ages mothers loved their children any less than they do now. However, I do believe this love was not exhibited in the same ways. Tracy Adams argued that women were perceived to not love their children as a result of their position in society and their lack of power in the household that reflected upon the power they wielded over their offspring. As women were unable to have a definite say in the upbringing of children, they consequently chose to distance themselves from these children and allowed the dominant roles in the household to intercede as these women subsequently removed from themselves all control or position in a child’s life. Ultimately this did not define the mother’s love for her children or the emotional attachment involved with the process that in this scenario seems completely irrelevant, but rather defines the societal demands placed upon the mother and child, specifically those outlined by Aries.

I think I may be defending Aries here, and if that is the case, then I do so only because despite that I feel his methods were rather faulty, I cannot help but pay homage to him as a pioneer in the study of the concept of childhood. Nor do I find many of his results to be inaccurate. In fact, starting an all out academic war against his theories is in itself a dated process. Yes, he was wrong on many fronts, but he was also equally right on just as many, and more importantly he paved the way towards the study of childhood – an objective that wasn’t terribly prominent before.

To fully understand this, it would be better to look backwards from the present day; you don’t even have to look far to begin seeing the discrepancies of child rearing between generations, and further, to tie this into the messages that children’s books focused on which should cast some light on the ways children were viewed. Before even attempting to delve into a historical analysis I will show a very modern, and personal example.

When I was little I distinctly remember having a book read to me that outlined how I was supposed to help my mother sew a dress. The imagination played no role in this type of book (one of many), while today I read to my daughter about talking ponies forming friendships. Both books have a moral, or lesson to be learned, but obviously one is more utilitarian than the other. Arguably social skills are just as important as sewing skills, but the difference is in the expectation on children’s behavior. My daughter is taught social skills as a means to making friends and spending her time playing with them, while I was taught how to sew (albeit for reasons unknown since I can barely reattach a button), and, if memory serves me correctly, how to iron. However, this brings forward another question: do modern day children lack social skills, or did children in previous eras lack them due to paucity of materials delineating proper social behavior? I believe the answer illustrates not only how the expectations placed upon children have changed, but also serves to trace the types of environments children lived in.

For example, in my modern day anecdote I was not taught via anthropomorphic horses how to relate to other little girls my age because it was understood I would learn these skills through the experience of interacting with others on a very regular basis from a very early age. My children on the other hand have the advantage (depends on who you ask) of being in daycare where they too learn these skills, but for those children who are not in a school setting until six or seven when they attend elementary school, today’s society does not always offer much in the way of interaction. Children as young as four and five are not allowed to roam the streets and neighborhood park and play until sunset lest their parents wish to either be arrested or have their custody taken away, or both.

I understand I am diverging greatly from my original topic and this hardly has anything to do with medieval childhood, but I wanted to point out the disparity in ideology between even two very modern times in order to segue into the ways children were treated and what was expected of them in much earlier periods (and what better way to smoothly segue and transition than to blatantly tell you I am doing so?).

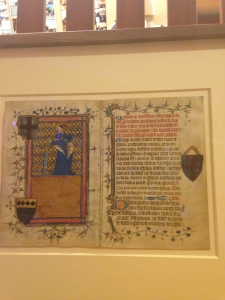

The Auchinleck manuscript, often known for its hagiographical texts, also houses a very personal aspect of medieval history – the family dynamic. The Seven Sages of Rome, central to the manuscript is ripe with implication of an intended audience for the manuscript that is perhaps not at first perceivable – the family, and consequently a younger audience within this unit. Once again to pull you into our modern times and provide a parallel example, think of the multiple youthful protagonists of our hero stories (now movies), and our coming of age tales, all catering to a young audience that is facilitated by the parents or caregivers who must provide this form of entertainment for the child.

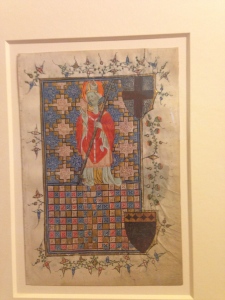

(Auchinleck MS, folio 326r – Since the Seven Sages contains no artwork outside of flourishes on the initials, here is an illustration from the segment on King Richard within the Auchinleck – depictions of kings and knights in medieval manuscripts were just as appealing to children then as they are now)

Returning to Aries, he looked at the societal configurations of the medieval period, mapping the role of children in the home. Yes, children will play, their imaginations will get the best of them, but once playtime was over, they were also expected to fulfill certain roles that extended beyond keeping their rooms neat and picking up their toys. Children as young as eight would be sent off to other homes to learn trades or pay off family obligations. And this was within what would be considered middle to upper class families. In poor families the children were simply expected to earn their keep. No one had time for fantasy when there was water to be brought, bread to be made, wood to be cut, laundry to be beaten, and numerous other chores. This is not to say that children performed all or any of these chores, but much like I was taught to sew (to little avail) when I was four or five, so were these children shown much more difficult tasks at young ages as a means of exposure for future use. Basically everyone had things to do, and the nuclear family as we perceive it today was just not there, nor did the modern dynamic exist.

I have to briefly pause here and mention the overwhelming number of references I found to hagiographies of children while conducing this research. While there is no apparently neat way of inserting my findings here since they appear to be completely unrelated to the rest of this brief analysis, I have to remark that this may not be fully accurate. Child hagiographies, for their myriad abnormalities of realty, shed light upon the distinction between reality and the desired, and thus demonstrate the reality of childhood in the Middle Ages via various means of negating those traits that appear superfluous or unrealistic. In short, through carving away the unbelievable we are left with a rather accurate portrayal of childhood.

More over, as education began to gain importance, so did the idea that children were not simply miniature adults, but rather the future of society. Once public (for those of you across the pond, private) and more or less standardized education became prominent, this idea of the child as something special took hold. Children, long before holding the title of heirs and being cherished for the upholding of the blood line, became the gateway to the future in a broader, globalized sense where the child was seen as the conduit for future generations and what would be invested in the current generation of small children would benefit others later on. This altruistic stance was not easily adapted, and the time in which it became well practiced is still under debate, but it appears that around the seventeenth century education overthrew the desire to create trade workers. Thus another facet of caregiving had its inception and educational progress became something to monitor, overreaching well beyond the higher classes into the wealthier middle classes who could nevertheless afford to educate their children as opposed to sending them off to work.

As a newly educated class of children emerged so did the family dynamic shift. Children had fewer chores, more study time, and if logic serves properly, these chores still needed to be completed, leading to families seeking out solutions for their needs. The socio-economic implications of educating children is well beyond the scope of my research, but I have a hunch that broader education shifted much of the ways employment functioned from as early as the twelfth century onward.

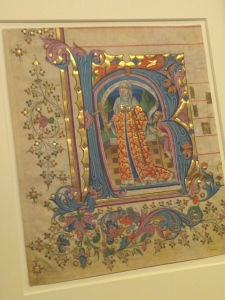

Yet, it is during this period when children began an education that the materials used to educate them became scrutinized. Books were not owned in the dozens, and only some children had the luxury of hailing from literate families in the early middle ages. Even so, those who owned books had few specifically designated for small children who were often left to navigate family volumes, and were most likely quite entertained by illuminated manuscripts should any be available. While multiple manuscripts often had amusing miniatures, decorated initials, and bas-de-pages, one source in particular was terribly appealing to small children, the bestiary. However all of these sources functioned as distractions and didn’t often serve as formal instructional material.

(British Library, Harley MS 4751, f. 30v – clearly such images would entertain children, especially considering how much they already entertain adults)

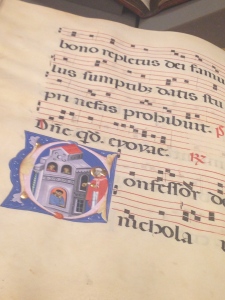

Educational material had been around for hundreds of years where Books of Hours, or Primers served as the primary pieces for instruction in various ways, from reading to forming a compendium of proper Christian behavior. Picture books or pictures in books had been optimal for the illiterate for decades, and even rolls designated to church settings often had miniatures embedded upside down in order to face the audience, properly spilling over the lectern during worship so those facing the front could see the pictorial depiction of the sermon.

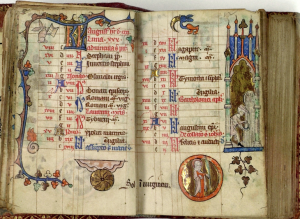

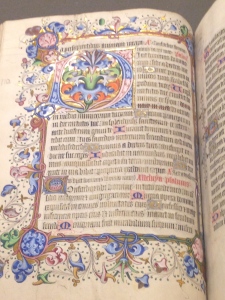

(Bridwell MS 13, Book of Hours, Hours of the Virgin, Calendar: August folios 9v-10r – Such decorated manuscripts served a twofold purpose to instruct and as can be seen from the types of decorations, to entertain. The various miniatures and marginalia contain important information such as the labor of the month, picking of the grain, and harvesting that are well connected with the month of August for those who cannot read the title of the month in red on the first line of folio nine. However, some images are solely there to serve decorate purposes, such as the creature at the top of folio ten, or the bunny, enlarged below, “reading” in the corner of folio nine)

(Bunny detail)

But little existed solely for children, especially in any sort of secularized milieu. Enter Child Lit. It was in no way recognizable to the children’s books we have today, but such texts provided enough information for small children. They were whimsical, colorful, and most importantly imparted moral teachings – essentially the medieval predecessors to our children’s books.

N.B. As I research this topic further I hope to find specific examples of medieval children’s lit, along with further historical evidence. In the meantime, I hope you enjoyed!

Sources:

Adams, Tracy. “Medieval Mothers and Their Children: The Case of Isabeau of Bavaria in Light of Medieval Conduct Books.”

Aries, Philippe. Centuries of Childhood.

Classen, Albrecht, Ed. Childhood in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: The Results of a Paradigm Shift in the History of Mentality.

Gies, Frances, and Joseph Gies. Marriage and the Family in the Middle Ages.

Hanawalt, Barbara. Growing Up in Medieval London.

Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Children.