This is the preliminary work conducted not just as part of my larger Chaucer Project, but specifically to be presented at the PAMLA conference at Riverside in October, 2014. Over the next few months I hope to have a more concrete idea of exactly where this is going, and which parts I am going to focus on, but for now, here is everything I have so far.

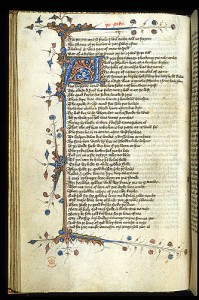

London, British Library MS Lansdowne 851 Folio 54v – beginning of the Tale of Gamelyn

Note: the random numbers in parentheses are meant to correspond to my sources. They are currently out of order.

The Tale of Gamelyn is the black sheep of the Canterbury Tales. Few have spent more time on it past dubbing it “un-Chaucerian” and “spurious” (8) while making various arguments against its authorship. Some Chaucer scholarship has so deeply seeped into tradition it has become irrevocable truth among medievalists, and unfortunately the idea that the Tale of Gamelyn was an addendum to the Canterbury Tales and not penned by Chaucer has suffered such a fate. However, when looking at several of the major strands of argument against the Tale of Gamelyn’s authenticity certain fallacies become immediately apparent and some previously perceived irrefutable answers only lead to further questions. Here I don’t just want to argue the Tale of Gamelyn’s authorship, but its origin and correct place within the tale order of the Canterbury Tales.

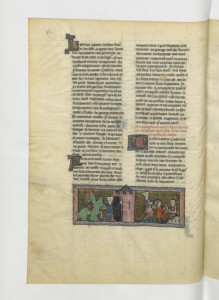

Scribal interventions played a crucial role in how manuscripts are analyzed and interpreted in modern times since the scribes supplied the end products as they are presently received. In the case of the Canterbury Tales, while Manly-Rickert entertained the idea that Chaucer provided more than just the text in the form of incipits, explicits, headings, and various marginalia (1) others believe only the actual tales to be his (2). Medieval scholarship in recent times has developed the convention of identifying scribes, tracing their works and making predictions about their lives in order to better attribute intentions to their emendations. When placed within this context, manuscripts cease being simply objects to transmit an author’s words and the organic processes undergone during manuscript creation becomes more of a concern than the end product of the actual manuscript. Therefore, when critics discredit Chaucer of having written the Tale of Gamelyn, it is implied that it may have been a scribal addition in line with the other scattered headlinks and endlinks throughout the Canterbury Tales. However, as will be explored, while this would not at all be unfeasible as an isolated manifestation in a single manuscript, the Tale of Gamelyn’s appearance within twenty-five manuscripts renders this theory very unlikely. Since scribes played a significant role within manuscript creation: they corrected simple errors; performed the medieval equivalent of fact checking; edited; provided incipits, explicits, and marginalia; and created or recreated material out of either necessity or preference (4) and further, because the Tale of Gamelyn does not appear in some of the early authoritative manuscripts, it could, but should not be concluded that the tale was a scribal addition, so well completed it maintained its place within several strands of manuscripts containing the Canterbury Tales for the better part of the fifteenth century (8).

Following, the majority of arguments against the Tale of Gamelyn being a part of Chaucer’s oeuvre focus on its absence from various authoritative manuscripts, including the Hengwrt and Ellesmere, often conveniently overlooking that it does appear within several manuscripts that are considered a part of the early manuscript category (Corpus, Harley and Lansdowne), coming from a similar time and place and which include and exclude tales in their own right (5), independently of previously created manuscripts; the Tale of Gamelyn exemplars were circulating along with Chaucer’s other works in different parts of the country simultaneously and its inclusion in almost a third of the Canterbury Tales extant manuscripts cannot therefore be deemed a simple scribal miscommunication (3). However, it has been argued that four of the most authoritative extant manuscripts (Ellesmere, Hengwrt, Harley 7334 and Corpus) were primarily worked on by two scribes who most likely knew each other, and may have collaborated on creating the exemplars, or at the very least shared information. Scribe D, responsible for the Harley 7334 and Corpus manuscripts, authoritatively inducted the Tale of Gamelyn into the list of tales and through this addition began the tradition of inserting it, accounting for the numerous manuscripts that followed and that also included the tale (8).

Yet, unlike other additions to the Canterbury Tales, along with other manuscripts for which this kind of argument could be made, attributing this tale to another (scribe, or editor) who would be attempting to form more cohesive bonds between tales actually obscures the reasoning further since it most certainly does not make the text as a whole easier to read – the tale’s oddity actually makes the linking process more difficult, hinting at possible reasons for its initial exclusion from the Chaucer canon. As far as tale ordering is concerned, the process is less convoluted without the Tale of Gamelyn. However, when regarded properly, it will be evidenced that the tale does share a place amongst the others, fitting in almost seamlessly which is to say it belongs exactly where it is placed, since unlike other tales its place does not shift between manuscripts. In fact, even within authoritative manuscripts, such as the aforementioned Hengwrt and Ellesmere, that do not contain the Tale of Gamelyn, there appears to be space allotted for additional material at the exact place where the tale is found within other manuscripts.

Another strand of argument against the Tale of Gamelyn’s authenticity takes into consideration its broad circulation, but stipulates that it must have gotten mixed in with Chaucer’s works and found itself inserted into the manuscripts through distribution of the exemplar since it could not be identified as un-Chaucerian to the untrained eye, especially because nothing else like it existed at the time, making it difficult to attribute the work to a different author (6). However, only part of this argument is correct as nothing else like it was in existence. Skeat formed various connections between the Tale of Gamelyn and a few other sources written during the reign of Edward III, but even he concluded that these similarities were shallow at best and the tale is unique, having been written with few if any previous inspirations (7). In fact the Tale of Gamelyn has been the influence for many later famous works such as the tales of Robin Hood, Rosalynde, and As You Like It. However this neither adds nor detracts from the “did Chaucer write this?” question.

Nevertheless it is its originality that casts doubt among critics as to Chaucer’s authorship. The majority of his works were either adaptations of previous narratives, or had clearly transparent points of influence. Yet when looking at the Tale of Gamelyn as un-Chaucerian based on its utter uniqueness, the underlying assumption is that Chaucer was incapable of creating original work. Aside from the adaptations of previous narratives, his other stories were his own. Simply because he was influenced does not detract from his talent or ingenuity, and the fact that he could take an idea or line from another work and reconfigure it into a whole new tale should actually attest to this. However, what this paper will shortly evince is that the Tale of Gamelyn, despite its original narrative, is actually just another example of appropriation and recycling of old ideas.

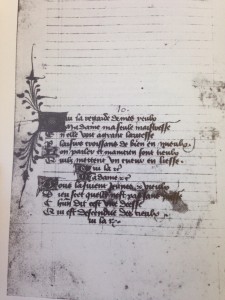

The last well known argument against Chaucer having written this tale, and the one with perhaps the most merit, relies on the metrics of the tale. It is written in a line form and scheme unlike anything else within the Canterbury Tales, and

Skeat noted “the variableness of the metre” (1884, p. xxiii), which is not as simple as Sands suggests in calling it a “seven stress affair” (1966, p. 156). That implies a line of four stresses before and three after the caesura which, as the poem is in couplets, could be taken as a version of ballad meter. But both the actual state of the meter and the frequency of four line syntax units (longer than a ballad stanza) refute this possibility. Skeat noted that many first half lines have three stresses, and this is more visible in the sparer, less scribally inflated, style of the Petworth manuscript, where three stresses before and two after the caesura is the norm, with a number of unstressed or half stressed syllables frequently added, and the occasional “heavy” line. This makes the meter not unlike that found in alliterative poetry, and there is a recurrence, though no regularity, of alliterative phrasing in the poem (9).

Nevertheless, when running searches for Chaucer’s most commonly used words, the frequency within the Tale of Gamelyn does not differ from other tales or parts of manuscripts. Neither does his preferred spelling (accounting for the disparity of spelling practices at the time) (10). So when the scheme and appearance of the Tale of Gamelyn are questioned, what is being referred to is the difference between it and other medieval texts, even those attributed to Chaucer – it is written in middle English, sounds very much like other parts of the Canterbury Tales, but relies on Old English conventions – thus the Tale of Gamelyn is yet another example of appropriation. Not unlike in previous stories where Chaucer reworks a theme, a few lines, or an entire tale, here he is recreating an earlier story and experimenting with style.

The Tale of Gamelyn is Chaucer’s version of the medieval Romance, and to draw out the parallels we will look at one of the earliest such stories, Beowulf. Even as Chaucer more than likely never read Beowulf himself, it is one of the oldest and best known examples that stands to represent the genre. Its basic elements have been replicated multiple times with varied, yet similar effects, and here we will dissect it piece by piece.

Before proceeding further, this is a (brief) translation of the introduction to Beowulf and the Tale of Gamelyn from MS Lansdowne 851 (the version I have chosen to use as my base text). [FOOTNOTE: The exemplar used for the Lansdowne manuscript appears to be very close to that of the Corpus Christi manuscript, and although La is considered a C manuscript, it is also one of the most complete within the early manuscript tradition that also includes the Tale of Gamelyn (13)]

Beginning of Beowulf:

So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by

and the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness.

We have heard of those princes’ heroic campaigns.

There was Shield Sheafson, scourge of many tribes,

a wrecker of mead-benches, rampaging among foes.

This terror of the hall-troops had come far.

A foundling to start with, he would flourish later on

as his powers waxed and his worth was proved.

In the end each clan on the outlying coasts

beyond the whale-road had to yield to him

and begin to pay tribute. That was one good king.

Afterwards a boy-child was born to Shield,

a cub in the yard, a comfort sent

by God to that nation. He knew what they had tholed,

and long times and troubles they’d come through.

Without a leader; so the Lord of Life,

The glorious Almighty, made this man renowned (11).

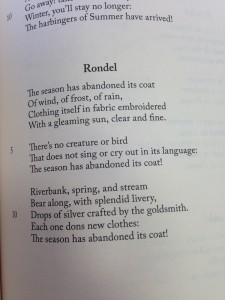

Beginning of the Tale of Gamelyn:

And pere fore listen . & herkenp pis tale ariht .

And 3e schullen here of a douhte knyht

Sir Iohn of Boundys was his name

He coupe of nortur & muchel of game

pre sonnes pe knyht had & wip his body he he wane

The eldest was a muche schrewe & sone he begane

His breperen loued wele here fader & of him were agast

The eldest deserued his fadre curs & had it att pe last

The good knyht his fadere leuede so 3ore

That depe was comen him to & handeled him sore

The goode knyht cared sore seke per he leye

How his children schold leuen after his deye

He had bue wide where bot no husbonde he was

Att the londe pat \he/ had was verrey purchas (12 – MS La)

The similarities are first apparent in the language used to begin both tales that are an introduction of the characters and how they have come to their position as we find them. The characters’ importance are set up according to lineage, and the story continues from there into separate episodes within great halls, and throughout the outskirts of the kingdom (swampy lake grounds vs. the forest) where feats must be accomplished and enemies vanquished through prowess, heroism, and sometimes trickery in order to maintain status and safeguard the seat of power. As Robert Bell has stated, such inclusions are in line with the Anglo-Saxon traditions that have long been popular with the peasantry. Moreover the convention maintains the oral tradition as the Tale of Gamelyn’s “And pere fore listen” is a direct echo of Beowulf’s “So,” which is appropriate for the purposes of the Canterbury Tales where each teller orally relates a story to the group. Arguably, the Tale of Gamelyn is better suited to this purpose than a majority of other tales on the pilgrimage making use of the practice of repetition and alliteration to aide with the memorization process that would have been necessary to deliver the tale from memory.

As the stories continue, the heroic/action episodes are interspersed with times of peace and leisure, lapsing in time respective to the length of each story; whereas Beowulf spans a lifetime and can be afforded many years of reprieve, the Tale of Gamelyn, a much shorter tale, is allowed only days and weeks. But everything from Beowulf’s form and style to narrative movement is mimicked in the Tale of Gamelyn on a smaller scale.

While Beowulf contains myriad characters (many of which are mentioned solely for maintaining the convention of an extended outline of lineage), there are key characters that are paralleled between both stories. From the beginning Shield Sheafson “weox under wolcnum,” (flourished later on as his powers waxed) proving his merit, and is shown as a “god cyning” (good king) for his various feats before his descendants are named, much as Johan of Boundys is introduced as a “douhte knyht” who “had bue wide” and whose “londe pat he had was verrey purchas” before his own heirs are announced. While neither of these characters figure in their respective stories, it will be through their lines of descent that the framework for both narratives takes place. Shield Sheafson’s descendent through several generations, Hrothgar, allows for the current situation in Denmark to exist since it is his hall, Heorot, that bids Beowulf’s arrival and sets into motion his enterprise. However, Hrothgar has his own parallel role to fulfill much like the unnamed king in the Tale of Gamelyn. Both men enable the fame of the heroes so that they may, after fulfilling their feats, rest in peace, even as the stories here departure from each other allowing Beowulf fifty years of reprieve before his last feat, as opposed to the lifetime Gamelyn earns after performing his duties. Regardless, the seal of approval from the highest power in the land, the king, is seen as an emblem of accomplishment since the king stands in for the voice of the people thus globally condoning the activities of the two champions and making clear the lens through which their violent behavior should be regarded.

In addition, for the appropriate pictures of the heroes to be created, the malevolent entities threatening their respective realms must be properly represented in conjunction with the background of the territories that the heroes must fight to rescue and protect. Moreover, it must be noted that the Tale of Gamelyn has been depicted as the first outlaw chronicle by Knight and Ohlgren (9 again). While their argument is beautifully orchestrated, here the parallel between the Tale of Gamelyn and Beowulf relies on the notion of maintaining order and returning the land from chaos – a point made evident by the king’s approval at the end. While Knight and Ohlgren’s assertion regarding the Tale of Gamelyn’s status as an outlaw is correct, Robin Hood, to whom they make the connection is a descendant from this tale much like this tale is derived from Beowulf, which is still primarily concerned with mitigating threats against order. Thus once the present state of affairs is established it stands that both lands are distressed – either tormented by Grendel for twelve years as he takes over Heorot, or ruined into poverty by Johan. The heroes of the stories (Beowulf and Gamelyn) embark on a mission to recapture lost grounds (Heorot and Gamelyn’s land). Beowulf attests to his physical prowess through oral eloquence and relies on stories of his past to convince those he meets while Gamelyn demonstrates his physical strength through a wrestling match – a point of relevance later on. Beowulf slays Grendel and then they feast. Gamelyn defeats the men Johan sets upon him, has Johan locked in a tower, and then they feast. Grendel’s Mother comes to seek vengeance against Heorot and the men within, aiming to retributively destroy Beowulf. Johan enacts revenge against Gamelyn. Beowulf, in an incredibly bloody battle slays Grendel’s Mother. Gamelyn, in a fury and fit of violence strikes down several men and has Johan bound. Beowulf departs back to his land where, after reprise from physical activity he becomes king. Gamelyn departs into the forest, spends time with a band of outlaws and becomes their king.

However, the time of peace does not last long before a dragon in search of his treasure begins tormenting the town, causing Beowulf to once again take action. Gamelyn’s remission is disturbed when he hears of Johan’s newest atrocities against the people who all now live in complete shambles and poverty, moving Gamelyn to take action and return to his city in order to restore order. Beowulf, with Wiglaf’s help slays the dragon. Gamelyn, with Ote’s help puts an end to Johan’s tyranny. Lastly, Wiglaf becomes Beowulf’s heir, and Ote inherits the lands his father had intended for him to have.

At this point the stories diverge and whereas Beowulf dies, Gamelyn is rewarded by the king, thus inverting the story during the third part as Gamelyn gains his glory after his third endeavor at heroics, as opposed to Beowulf’s prolonged peace, which he finds between the second and third ordeal. However, the difference in ending makes sense considering the Tale of Gamelyn’s overall purpose. The tale has been categorized as a Romance (15), and even if only barely applicable, it still appears to be a stretch. Yet under this nomenclature, for Gamelyn to die or incur punishment would seem remarkably unwarranted, harsh, and unnecessary. Chaucer’s contemporaries would feel somewhat disengaged from things such as blood feuds and the celebration of violence in what professes be an elite society – concepts that combine rather awkwardly with Christian perspectives that honor an allegory of salvation and ideals about humility. In fact, one of the qualities Chaucer is best known for is being one of the first writers in the English language during the medieval period to really promote vernacular language and more importantly local concerns within his writing, as opposed to a lot of his contemporaries who chose Latin, French, and Italian.

Thus while Chaucer readapted the Romance genre, he (per usual) superimposed several other themes into the story, and since Romance seems to be an inaccurate label, a perhaps more suitable one would be to call the tale a roman d’aventure (16). This too serves as a link between Beowulf and the Tale of Gamelyn as they operate within the same genre, but cater to different audiences. The roman d’aventure differentiates between the matters of heroism of a French nation, which are typically enclosed in a chanson de geste, and those of the British that heavily rely on the epic hero tales, far removed from the everyday concerns of hoy polloi who will never encounter men of such grandeur, and who are not necessarily at ease with some of the implications of the warrior culture that overemphasizes the concept of glory. Chaucer succeeds in reconceptualizing Beowulf, readjusting the individual points for a modern audience as the narrative arcs remain congruent, moving away from the Anglo-Saxon epic to a romanticized version of heroism more appropriate for a fully Christianized era. This too is apparent from the beginning of both tales, recalling the catalogue of lineage that is used to introduce the characters. Whereas the Anglo-Saxons were oriented towards kinship and family to define the individual as indivisible from the group, the Christian era (without negating that Beowulf straddles and combines the pre and post Christian traditions) placed greater value on the soul, and consequently the individual as evidenced in the description of the personages. Beowulf comes from a line of nobility while Gamelyn’s line is significantly shorter, denoted by the description of his father’s “londe pat \he/ had [which] was verrey purchas,” meaning he was a self-made man, and any lineage Gamelyn may claim stops only one generation before, especially considering that his father’s father only possessed “plowes fyue.” As previously mentioned, Beowulf’s genealogy operates as his credentials when entering the Dane’s land, while Gamelyn must prove his worth physically, by himself.

Yet while these parallels may appear obvious, and even convincing, Chaucer’s authorship remains questioned. If he translated French and Latin and adapted from Ovid, Dante, and Petrarch (17), among others, then why is it so far fetched that he would look towards accomplishing the same ends with Old English texts? Further, there is absolutely no record of this tale being told anywhere else in medieval Europe (18). No other known author used this exact style, and even those opposed to Chaucer’s authorship for the tale will concede a similarity within the text to Chaucer’s hand. A few theorize that he did intend to use it in the Canterbury Tales, but had not yet finished making changes to it, with the implication that there was a text out there who no one other than Chaucer ever saw or knew about, and he was in the midst of copying it for his Canterbury Tales but never finished. While this is not impossible, it is highly unlikely. Few, if any dispute that the Tale of Gamelyn was within Chaucer’s stack of papers at death, but rather, they challenge his authorship or whether it was intended for the Canterbury Tales.

However, even in deciding Chaucer wrote the Tale of Gamelyn, and meant it for inclusion within the Canterbury Tales, there remains the question of its place within tale ordering. Every manuscript that contains the tale places it after the unfinished Cook’s Tale, which has in turn lead all those in favor of Chaucer’s authorship to stipulate that it was meant to belong to the Cook. Either the Cook would have a second tale, much like Chaucer the pilgrim (Thopas and Melibee) since just like Chaucer, the Cook did not finish his first tale, or as others speculate, the Tale of Gamelyn was meant to replace the unfinished Cook’s Tale.

The Cook, much like his tale, is incomplete. He is a character thrown in to serve a narrative purpose for others. He is the embodiment of the material wealth the five guildsmen possess, and just as unclean as the origin of their money. They may have had the wealth to pay a personal cook, but according to his description in the General Prologue and his later personal prologue, he is far from a private chef. Money does not breed discernment. As the Host later notes, his food is practically inedible, he is a churl worse than the Miller and Reeve combined, and on several occasions he must be awoken by others from his drunkenness, with even a slight hint that his tale is unfinished because he was physically incapable of completing it. In other words, this is not the man telling the complicated Tale of Gamelyn.

The second most popular claim for the Tale of Gamelyn is made in favor of the Canon. Since so little is known about the Canon who appears with his Yeoman out of nowhere, this is not an impossibility. However, I would like to propose that the Tale of Gamelyn is generally (with only one exception (19)) found near the top of the manuscripts for three reasons: it was meant to be its own fragment, to follow the Cook’s Tale, and it was told by the Yeoman (not to be confused with the Canon’s Yeoman). This last part has been previously addressed (20), but for different reasons, and consequently has been refuted. However, in following a progression of proper evidence it can be shown that the Yeoman as tale-teller leads to a logical conclusion.

To begin, according to an already established temporal scheme (20), the Man of Law’s Tale would be the first tale told on the second day of the trip. Thus Fragment I, preceding the Man of Law’s Prologue remains intact and ends on the first day. In between these two is where the Tale of Gamelyn is typically found because it was meant to be told at dusk on the first day, before the Man of Law would pick it up again the next morning. As previously mentioned, the Tale of Gamelyn does not neatly fit into any of the other sections, however, it does make for a good evening tale, especially when a complete theme is not yet established and groupings are not as of yet fully formed, pointing towards the beginning of the manuscript as an ideal position where order is yet an experiment and individual tales and/or fragments may be switched around. Also, from the first tale told it is apparent that the Canterbury Tales will be a compilation of new and previously written pieces considering that the reference to Arcite and Palemon acts as evidence that that Knight’s Tale was written before the General Prologue since these two characters were previously found in the Legend of Good Women (21). There is a good chance that Chaucer initially created the Tale of Gamelyn for another enterprise, but decided to include it into the Canterbury Tales, providing another reason it is separated from the other fragments. Having been loose from the rest it was easy to transfer. Nevertheless, it was to be included, and its placement within his papers at the exact place it appears or where room is left for a tale to be inserted is a reflection of where he intended it to go, despite not having yet assigned a character to tell it.

By process of elimination the best candidate for this tale, who has not yet told one, is the Yeoman. There is absolutely no indication of this throughout the Canterbury Tales, and there is no prologue to the Tale of the Gamelyn. The “return trip” argument will here remain untouched, not because it lacks merit, but rather because it needlessly complicates matters. So given that everyone was to tell at least one tale, from the pilgrims left within the General Prologue who have told no tale within any manuscript, the only ones left are the Yeoman, the five guilds men (Haberdassher, Carpentere, Webbe, Dyere, and Tapecere), and the Plowman.

The first and easiest to immediately eliminate would be the somber Plowman, whose brother, the Parson, gives a lengthy sermon on morality at the end. It would be quite a stretch to turn the Tale of Gamelyn into a morality tale, or overlook its violence. And while the Plowman would not necessarily be obligated to tell a tale in line with his brother’s, their descriptions in the General Prologue would insinuate otherwise.

As for the five guilds men, they are in the same class as the Merchant, but obviously better off financially than he is. While the praise they receive from the Host for their devotion to material goods is clearly satirical, it is more a commentary on the rising middle class of the day. This is a very elitist unfavorable portrait of this new station. However, in classifying them as such, it becomes unlikely that any one of them would tell a tale concerning noble lineage and inheritance. As aforementioned, Gamelyn did not descent from a long line of nobility, but nevertheless operated in accordance to the codes of the upper class – through his father’s accrual of land he found himself among the gentry. Moreover, his concerns were not monetary as much as concerned with justice and power that seem in line with the desires of the newly established middle class, but actually function differently in accordance with the codes of gentry. These five guildsmen would be unable to empathize with these matters of inheritance and law precisely because they have none and their class prided itself on having risen from nothing, from which Gamelyn is now removed.

This leaves the Yeoman, who is not wholly touched on in the General Prologue, but the seventeen lines attributed to his attire speak volumes. He is clearly a woodsman, a keeper of game, but his fine array of clothing place him close to wealth with the not so subtle indication that he may have acquired his wealth through less than moral means by stealing from precisely those he had promised to protect. While there have been discussions as to whether he is the Knight’s or the Squire’s yeoman, the most pertinent part of his position is that he possesses the manhood that both of these characters have displaced (22). As the keeper of masculinity for the now too fatigued Knight, and the all too boyish Squire, he occupies their space and it would be most fitting for him to tell a tale in which a fellow inhabitant of adjacent forests is championed and restored to society through his own acute prowess while gaining prominence for his feats and being allowed to maintain a socially condoned high ranking post among those in the woods. It is well recognized that the Tale of Gamelyn was a (if not the) predecessor to the Robin Hood tales, and thus allows for the fantasy that conflates outlawry with justice and acceptance.

Lastly, considering the Yeoman’s position in the General Prologue and reemphasizing how the early parts of the Canterbury Tales most likely lacked the same definition of theme found in later parts, it would be fitting for his tale to reside between the Knight and Squire, appropriate according to the ambiguity of his employment while also loosely functioning in line with the idea of chivalry and courtly comport (or the commentary in regards to such behavior) that is found within the neighboring tales.

Arguments for better placements of the Tale of Gamelyn may be made, but thus far the textual evidence of the plot and physical condition of the manuscripts suggest that the tale was very plausibly left along with other exemplars to be included not just within the Canterbury Tales, but in its current position, and told by the Yeoman. There is less to gain in attempting to refute this, but much to learn by looking at the twenty five witness manuscripts confirming it.

Sources (as they appear numbered in parentheses):

1. Manly, John Matthews, and Edith M. Rickert, eds. The Text of the Canterbury Tales, Studied on the Basis of all Known Manuscripts. 8 Vols. (primarily used Vol. 2)

2. Owen, Charles A. “Pre-1450 Manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales: Relationship and Significance. Part I.” The Chaucer Review. 23.1 (1988): 1-29.

3. Vasquez, Nila. The “Tale of Gamelyn” of the “Canterbury Tales”: An Annotated Edition. Wales: The Edwin Mellon Press, 2009.

4. Fisher, Matthew. Scribal Authorship and the Writing of History in Medieval England. Ohio: UP, 2012.

5. Owen (“Pre-1450” again) and Stubbs, Estelle. “‘Here’s One I Prepared Earlier’: The Work on Scribe D on Oxford, Corpus Christi College MS 198.” The Review of English Studies. 58.234 (2007): 133-153.

6. Skeat, Walter W. ed. The Tale of Gamelyn. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1884.

7. Skeat, Walter W. The Tale of Gamelyn from the Harleian MS no. 7334, Collated with Six Other MSS. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1893.

8. Thaisen, Jacob. “The Merchant, the Squire, and Gamelyn in the Christ Church Chaucer Manuscript.” Notes and Queries. 55.3 (2008): 265-269.

9. Knight Stephen, and Thomas Ohlgren. eds. Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

10. Thaisen, Jacob. “Gamelyn’s Place among the Early Exemplars for Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.” Neophilologues. 97.2 (2012): 395-415.

11. Heaney, Seamus. Beowulf. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000.

12. London, British Library MS Lansdowne 851. (partly digitized and the rest transcribed)

13. Horobin, Simon. The Language of the Chaucer Tradition. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2003.

14. Bell, John. The Poets of Great Britain from Chaucer to Churchill. London: Printed for J. Bell 1777-79. 109 Vols.

15. Ramsey, Lee C. Chivalric Romances: Popular Literature n Medieval England. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1983.

16. Comfort, William Wistar. “The Essential Difference Between a Chanson de Geste and a Roman d’Aventure.” PMLA. 19 (1904): 64-74.

17. Fisher, John. The Complete Poetry and Prose of Geoffrey Chaucer. Tennessee: UP, 1977.

18. See Skeat, 1884.

19. Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Hatton Donat. 1 (partially digitized)

20. Brusendorff, Aage. The Chaucer Tradition. Oxford: UP, 1925.

21. Cooper, Helen. “The Order of the Tales.” The Ellesmere Chaucer: Essays in Interpretation. San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1995.

22. Scala, Elizabeth. “Yeoman ServicesL Chaucer’s Knight, His Critics, and the Pleasures of Historicism.” The Chaucer Review. 24.2 (2010): 194-221.