So this is the first draft of a proposal. It is not yet edited, but I should have it done and submitted in the next week. Any feedback is welcome.

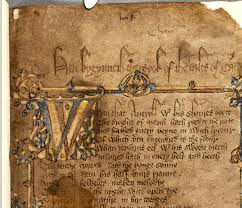

Any scholar working with the Canterbury Tales will immediately be faced with the question of tale ordering as proposed by the different extant manuscripts – a topic which has only gained more prominence since the appearance of the Manly-Rickert 1940 volumes that greatly facilitated textual comparisons. Theories on tale orderings abound, and while true authorial intent remains unknown, and perhaps unknowable, some theories appear to be better than others. This paper will argue that while each existing witness manuscript provides a piece of the puzzle, there is yet another order that appears nowhere within the manuscripts and has not been adequately addressed, but when regarded in terms of paleographic and contextual evidence deserves closer examination and consideration. Specifically, this paper proposes a rearrangement of what are currently considered Fragments VI and VII. The argument is twofold, first providing an explanation of how the Shipman’s Tale has made its way towards the end of the tale ordering, while simultaneously justifying its connection to the other five tales within its fragment (despite its exclusion from numerous manuscripts). Once the Shipman’s Tale is established, it will be shown that fragment it belongs to can be neatly divided into two when following a logical narrative path, while moving the second trio in this segment closer to the Franklin’s Tale in Fragment V since I believe the latter of this threesome was inserted within the Fragment II for lack of a better place to put it, and based on cursory evidence made to fit, despite clues that connect it to Fragment V.

In conclusion, the newly proposed tale ordering is as follows:

Fragments 1-5 (as depicted in Ellesmere and most other authoritative manuscripts) ending with the Franklin’s Tale

Fragment VII(second trio) – Prioresse-Thopas-Melibee

Fragment VI- Physician-Pardoner

Fragment VII(first trio) – Shipman-Monk-Nun’s Priest