I am still working on Lydgate’s “A Complaynt of a Loveres Lyfe,” and will resume from where I left off. Here I am only posting preliminary notes, and observations that I find useful, but if you are interested in the poem, visit my sources for far more in depth discussions. In the meantime, enjoy!

But this welle that I her reherse

So holsom was that hyt wolde aswage

Bollyn hertis, and the venym perse

Of pensifhede with al the cruel rage,

And evermore refresh the visage

Of hem that were in eny werynesse

Of gret labour or fallen in distresse.

After Lydgate references the multiple bodies of water that are unlike this well, he proceeds to explain its wholesome and restorative nature as it ameliorates anger, rage, wariness, and general distress.

And I that had throgh Daunger and Disdeyn

So drye a thrust, thoght I wolde assay

To tast a draght of this welle, or tweyn,

My bitter langour yf hyt myght alay;

And on the banke anon doune I lay,

And with myn hede into the welle araght,

And of the watir dranke I a good draght.

The narrator wishes to partake in the qualities of the water, and drink a drop or two to assuage his own maladies. Daunger signals the reference to the Romaunt, further carried out across the stanza until the last lines that clearly indicate a verbal parallel between the Romaunt and this work, essentially reminding the audience of the lover who is about to enter into the foreground of the poem.

Wherof me thoght I was refresshed wel

Of the brynnyng that sate so nyghe my hert

That verely anon I gan to fele

An huge part relesed of my smert;

And therwithalle anon up I stert

And thoght I wolde walke and se more

Forth in the parke and in the holtys hore.

The narrator is indeed relieved from the burdens within his heart, and he decides to continue walking to see what else this land holds. Interestingly, he describes the place in terms of a “holtys hore” that in numerous works such as the Roman, the Romaunt, Sir Orfeo, and Launfel, (among others) are words used to describe wild, desolate places. “Holtys,” the woods, take on a dreary description of unpleasantness, tainting the earlier image of a paradisal garden intoning love and whimsy. By the end of the stanza the restorative well which serves to sooth the soul seems almost out of place.

And thorgh a launde as I yede apace

I gan about fast to beholde,

I fonde anon a delytable place

That was beset with trees yong and olde

(Whos names her for me shal not be tolde),

Amyde of which stode an erber grene

That benched was with clourys nyw and clene.

The narrator continues walking and finds a pleasant place containing trees that will remain unnamed, in complete contrast to the earlier encounters with trees that bore names referencing a series of ill matched pairs such as Apollo and Daphne, or Dido and Aeneas. At the end of the stanza he comes upon a mound of “benched” land, meaning a plot perfect for sitting, that was newly covered in grass. “Clourys” has been glossed as “colouryd” before, but covered makes the most sense. Here he shall sit as the rest of the poem unfolds.

This erber was ful of floures ynde,

Into the whiche, as I beholde gan,

Betwex an hulfere and a wodebynde,

As I was war, I sawe ther lay a man

In blake and white colour, pale and wan,

And wonder dedely also of his hiwe,

Of hurtes grene and fresh woundes nyw.

The narrator beholds the “floures ynde,” or blue flowers reminiscent of the ones in the Romaunt (line 67), before spying a man in black and white. This man is positioned between the hulfere, or holly, and wodebynde, honeysuckle. While the hulfere is inconstant across manuscripts, rendering a meaning more difficult, the honeysuckle has often been associated with lovers. It appears in the Knight’s Tale as Arcite makes a garland from hawthorn and honeysuckle. Troilus and Criseyde are entwined like honeysuckle in an embrace. Marie de France devotes an entire lai to honeysuckle in which she narrates a brief encounter between Tristan and Iseult. In every instance those represented in connection to the plant suffer heartache, death, or are somehow ill matched to their pair. As the man is spotted near the plant, it immediately signals troubles of love even before he is properly introduced via his own lament.

Here the poet remains hidden from view, eavesdropping, and stepping into the infamous role of poet as voyeur in which the private matters of the heart are translated into forms for public consumption by virtue of being witnessed and written down. Thus, as the narrator will begin relating what he sees and hears, the audience is implicated in the act of voyeurism.

Notably the man spied through the bushes is dressed in black and white in another Lydgatean nod towards Chaucer, specifically to the knight in Duchess. Lydgate will use this reference again in the Temple of Glas in which the lady’s outfit of black and white bears moral implications. The significance of color is made overtly clear in My Lady Dere: “And summe in token of clennesse, / Weren whyte. / But I, allas, in blak appere, / And alwey shal, in sorowe and dred” (lines 99-102). If for Lydgate white is purity, and Chaucer sees the Black Knight riddled with anguish, here the lover in the forest can be viewed as a pure and loyal lover, suffering from lovesickness, which, as discussed in an earlier installment of the poem, is a serious malady. To further drive the point, he is physically injured, and the pain from his heart mingles with the pain from his fresh wounds, producing an image of a hopelessly ill man, peaking our interest as we progress into the rest of the narrative.

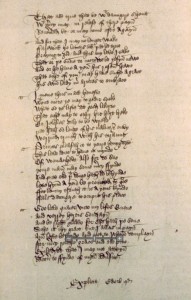

(Chaucer’s Complaint of the Black Knight, MS Digby 181 f. 39r, for a better visual, visit the Bodelian digitized version).

And overmore destreyned with sekenesse

Besyde, as thus he was ful grevosly,

For upon him he had a hote accesse

That day be day him shoke ful petously,

So that, for constreynyng of hys malady

And hertly wo, thus lyinge al alone,

Hyt was a deth for to her him grone.

It must be noted at this point that the narrator does not actually know why the man is suffering. The audience can guess considering the numerous tropes surrounding the man which all point towards a lover’s anguish, but it has not been overtly stated. However, if we are to infer he is lovesick, it is unclear whether his physical wounds are a results of his mental state, leading to the kind of convalescence displayed in earnest by others like Troilus (as opposed to his feigned sickness), or if the man’s wounds were derived elsewhere. Nevertheless, he is a terrible sight. Here we shall leave him, and in the next installment we will find out more about our mystery man.

Sources:

Krausser, E. “The Complaint of the Black Knight.”

Leach, Elizabeth Eva. Sung Birds: Music, Nature, and Poetry in the Later Middle Ages.

MacCracken, Henry Noble, ed. The Complaint of the Black Knight. In The Minor Poems of John Lydgate.

Norton-Smith, John, ed. A Complaynt of a Loveres Lyfe. In John Lydgate, Poems.

Spearing, A. C. The Medieval Poet as Voyeur.