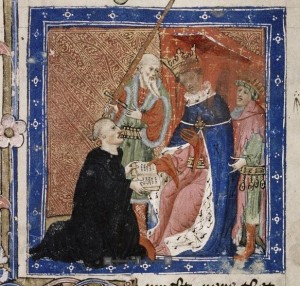

(Siege of Troy – Here Lydgate presents the work to Henry V. Oxford, MS Digby 232, f. 1a r)

In continuing with my look into Lydgate’s “A Complaynt of a Loveres Lyfe,” I will be resuming where I left off in my previous post. Per usual, each stanza will be accompanied by some of my brief thoughts, and at the bottom you will find my sources that delve much deeper into each topic.

And in I went to her the briddes songe,

Which on the braunches, bothe in pleyn and vale,

So loude songe that al the wode ronge,

Lyke as hyt sholde shever in pesis smale.

And, as me thoght, that the nyghtyngale

Wyth so grete myght her voys gan out wrest,

Ryght as her hert for love wolde brest.

Birdsong operates as an integral part of locus amoenus, drawing the reader into the enchanted world, while also drawing the parallel of birdsong in the Romaunt, Parlement of Fowls, and the General Prologue. These works all rely in part upon the connection between nature and humanity, and the constant contrast that sets the two apart in order to better understand the latter. Humanity may appreciate birdsong that is often associated with love, and the boundlessness of nature, but birdsong does not harbor the well calculated rhythm of music. Irrational creatures, birds, may not produce rational composition. In probing this analogy further, love, too, is understood as irrational, and its lure becomes dangerous.

The soyle was pleyn, smothe, and wonder softe,

Al oversprad wyth tapites that Nature

Had made herselfe, celured eke alofte

With bowys grene, the flores for to cure,

That in her beauté they may longe endure

Fro al assaute of Phebus fervent fere,

Which in his spere so hote shone and clere.

Once again the parallels to other paradisal gardens abound, as the poem clearly crosses the threshold into the land of love and dream visions. However, interestingly, here Nature is simultaneously chaotic as her boughs overflow and overtake the ground and flowers, while also utilitarian in using these seemingly unwieldy appendages to protect flowers from the destructive powers of Phebus, the sun.

The eyre atempre and the smothe wynde

Of Zepherus amonge the blosmes whyte

So holsomme was and so norysshing be kynde

That smale buddes and rounde blomes lyte

In maner gan of her brethe delyte

To gif us hope that their frute shal take,

Agens autumpne redy for to shake.

Every aspect of this world will be examined, including the climate. Similar lines will be echoed in The Siege of Thebes: “Zephyrus with his blowing softe / The wedere made lusty, smoth, and feir, / And right attempre was the hoolsom eir” (lines 1054-1056). Further, in Parlement, “Th’air of that place so attempre was / That nevere was grevaunce of hot ne cold” (lines 204-205). In short, temperature, climate, and Zephyrus, the west wind, are all commonly used throughout medieval texts to elicit the concept of an idyllic milieu, or at the very least to set the tone for one.

As the sun pierces the foliage, and the wind gently blows, the temperate temperature is perfect for an onslaught of blooming flowers being heralded in by spring, such as de Meun’s Zephyrus who, together with his wife Flora, create the flowers used to celebrate lovers (Roman lines 8381-8392). This brings to the forefront Zephyrus’s inclinations, and continues to position Lydgate’s poem within the realm of lovers. Love buds like the flowers engendered by Zephyrus’s breath, relying on the notion of the west wind as a general emblem for renewal and reanimation. Recall in Sir Gawain and the Greek Knight, Zephyrus is directly juxtaposed with the coming of winter (lines 517-525).

I sawe ther Daphene, closed under rynde,

Grene laurer, and the holsomme pyne,

The myrre also, that wepeth ever of kynde,

The cedres high, upryght as a lyne,

The philbert eke, that lowe dothe enclyne

Her bowes grene to the erthe doune

Unto her knyght icalled Demophoune.

The classification of trees appropriately commences with a reference to Daphne. For those unfamiliar with the story, Apollo mocked Eros for his use of a bow and arrows, causing Eros to demonstrate the power of his tools. Apollo, shot with a golden arrow, uncontrollably falls in love with Daphne, a nymph, who was pierced by a lead arrow designed to induce hatred. A chase ensues, and as Apollo is about to catch Daphne she calls for her father (sometimes Zeus, depending on the version) who then helps her by converting her into a tree to escape Apollo’s grasp. Specifically, a laurel. Thus in Lydgate’s poem she leads the procession of trees, each with their own meaning derived from previous legends and texts.

Trevisa’s translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus De Proprietatibus Rerum offers some very interesting descriptions for each of the trees featured here, along with their potential uses.

The last lines of this stanza reference another pair of ill fated lovers, casting a negative light upon the subject, while foreshadowing the knight the narrator will soon encounter. Here the filbert tree is a reference to Phyllis who was abandoned by Demophon, the son of Theseus and Phedra. On his way home from Troy, he was shipwrecked and Phyllis repaired his ships and entertained him. He married her, but then had to leave, promising to return, which he never did. Phyllis impatiently awaited his return, and when she could wait no more, she hangs herself on a tree. The gods pitied her and metamorphosed her into a tree. Interestingly in classic sources, namely Ovid, she transforms into an almond tree. And even though the story is mentioned several times by Chaucer in the Legend of Good Women, Duchess, Fame, and through the Man of Law, the only earlier instance of her being transformed into a filbert tree is derived from Gower’s Confessio, which also carries the closest narrative parallel to the Complaynt. Lydgate will later use these references in the Temple of Glass.

Ther saw I eke the fressh hawthorne

In white motele that so soote doth smelle;

Asshe, firre, and oke with mony a yonge acorne,

And mony a tre mo then I can telle.

And me beforne I sawe a litel welle

That had his course, as I gan beholde,

Under an hille with quyke stremes colde.

The foliage imagery continues into this stanza, and extends from trees to hawthorn, a sturdy and steadfast plant. Trevisa also has much to say about the plants mentioned here as he describes their properties and uses (see above).

The narrator than wanders towards a stream that flows from a well under a hill, much like the well that flows from a hill in the Romaunt. The water is cold and inviting, luring the narrator to drink.

The gravel golde, the water pure as glas,

The bankys rounde the welle environyng,

And softe as velvet the yonge gras

That therupon lustely gan spryng.

The sute of trees about compassyng

Her shadowe cast, closyng the wel rounde

And al th’erbes grouyng on the grounde.

The gravel in the Roman is “plus clere qu’argenz fins” (line 1527), and in the Romaunt it “shoon / Down in the botme as silver fyn” (line 1557). The rest of the lines in this stanza closely follow both of these works, echoing their words in the description of the well.

The “sute of trees,” referring to a set or series is the first recorded instance of the word used in this sense (OED). In the Romaunt the trees are planted in rows. In the Roman it is only the pine trees that cast a shadow. However, despite the similarities, unlike other wells (the well of Narcissus, Diana, or Pegasus), here the well has restorative properties, as we shall shortly see, and only resembles others in appearance.

The water was so holsom and so vertuous

Throgh myghte of erbes grouynge beside –

Nat lyche the welle wher as Narcisus

Islayn was thro vengeaunce of Cupide,

Wher so covertely he did hide

The greyn of deth upon ech brynk

That deth mot folowe, who that evere drynk;

The wholesome water has the power to sooth lamenting lovers, which Lydgate carefully makes evident when repeatedly telling the audience this well is “nat lyche,” “ne lyche” and “nor lyche” any of the others that are associated with spurned lovers, in the same vein as the earlier trees. The story of Narcissus also echoes a reference to Echo, who fell in love with Narcissus and was shunned, left wasting away until only her voice remained to repeat what she had heard. Narcissus is punished for his ill use of Echo and is cursed to fall in love with himself. As soon as he gazes upon his own reflection in the water he is mesmerized, living out the rest of his days staring at himself, and later turned into a flower. This transformation for Lydgate is a source of death – a useless infatuation that engenders nothing. Thus even as he follows in the tradition of the Roman, Chaucer who makes mention of Narcissus in the Knight’s Tale and and Franklin’s Tale, Gower in Confessio, and even Ovid who initially proposed the metamorphosis, Lydgate does not allow Narcissus to become a positive reference for love. Narcissus’s self love was grounded in a physicality that is generally not embraced in the Lydgatean world.

Ne lyche the pitte of the Pegacé

Under Parnaso, wher poetys slept;

Nor lyke the welle of pure chastité,

Whiche as Dyane with her nymphes kept

When she naked into the water lept,

That slowe Atteon with his houndes felle

Oonly for he cam so nygh the welle.

The reference begins with Ovid’s story of Pegasus, who stomped his hoofs into the earth, creating wells and springs, including Hippocrene that was sacred to the muses (said to have been located on the Heliconian peak of Parnassus). The importance here is the use for the well, to serve as an inspiration for the muses, which makes it unlike the well in the “Complaynt.” This well refreshes the drinker without proffering any other uses, least of all inspiration.

There is reason to believe the reference is solely placed here due to Lydgate’s affinity for these lines in classical literature, and a manuscript containing them in Persius’s Prologue to the Satires was found in the library of the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds. Lydgate also uses this passage within Princes and Troy.

The second part of the stanza relies on the story of Diana and Actaeon, another ill matched pair that leads to metamorphosis. Diana was bathing in a well as Acteon was out hunting. He gazed upon her, and consequently incurred her wrath. As punishment for his trespass she turned him into a stag, and he later was torn to shreds by his own hunting hounds. Here Lydgate is relying on Hyginus’s account in which the fountain Diana was originally bathing in, that initially commenced the series of events, was associated with chastity. This well is also unlike the Lydgatean well. Even as Lydgate might wish to distance himself from the erotic or physical nature of love, his distancing is more of a lack of mention as opposed to a true denial. Thus chastity would be out of place in this instance, and an altogether too strong opposition for love.

As he describes the locus amoenus, and he sets forth all that the well within is not, he has yet to define what it is, and why the audience should care. This is precisely what he sets out to do in the following stanza, and in my next installment of the poem, we will visit the well itself, and what it brings.

Sources:

Leach, Elizabeth Eva. Sung Birds: Music, Nature, and Poetry in the Later Middle Ages.

MacCracken, Henry Noble, ed. The Complaint of the Black Knight. In The Minor Poems of John Lydgate.

Norton-Smith, John, ed. A Complaynt of a Loveres Lyfe. In John Lydgate, Poems.