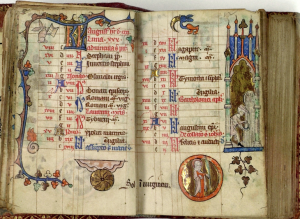

(Castelloza, BnF MS 843 f. 125 – this folio features the beginning of “Amics”)

While I don’t believe I am anywhere near done with my trobairitz research (can one ever be done with research?), I am on my final piece by Castelloza, and one which is all too often excluded from her oeuvre and disputed. Several scholars have over the years argued that this piece does not belong to her, especially since it only appears in one of the five manuscripts containing her work (Manuscript N). In many anthologies it is not included with her corpus, but rather attributed to Anon. at the end.

As I mentioned in a previous post, I have not yet conducted extensive overarching analyses on her work, largely because I had not yet finished working on each piece individually. However, after finishing “Per joi que d’amor m’avegna,” I want to believe it is hers, and herein lies my bias. So I am currently grappling with stepping away far enough to objectively work with the piece. All the evidence I am finding confirms my suspicions that I may have been initially overzealous; despite an already small oeuvre to work with, there are many stylistic differences between this canso and the other three.

Yet, before delving into the larger implications, here is my translation along with a brief analysis.

No m calgr’ ogan esbaudir

Qu’eu no cre qu’en grat me tegna

Cel qu’anc no volc obezir

Mos bos motz ni mas consos;

Ni anc nu fen la sazos

Qu’ie m pogues de lui sofrir;

Ans tem que m n’er a morir,

Pos vei c’ab tal autra regna

Don per mi no s vol partir.

Parti m’en er; mas no m degna,

Que morta m’an li cossir:

E pois noill platz que m retegna,

Vuilla m d’aitant obezir,

C’ab sos avinens respos

Me tegna lo cor joios.

E ja a sidons nu tir

S’ie l fas d’aitan enardir,

Qu’ien no l prec per mi que s teg

De leis amar ni servir.

Leis serva; mas mi’n revegna

Que no m lais del tot morir;

Quar paor ai que m’estegna

S’amors don me fai languir.

Hai! Amics valens e bos,

Car es lo meiller c’anc fos,

No vuillatz c’aillors me vir:

Mas no m volez far ni dir

Con ieu ja jorn me captegna

De vos amar ni grazir.Grazisc vos, cou que m’en pregna,

Tot lo maltrag el consir;

E ja cavaliers no s fegna

De mi, c’ us sol non dezir.

Bels amics, si fas fort vos

On teno los oillz ambedos;

E plas me can vos remir,

C’anc tan bel non sai cauzir.

Dieur prec e’ab mos bratz vos cegna;

C’ature no m pot enriquir.

Rica soi, ab queus sovegna

Com pogues en loc venir

On eu vos bais eus estregna;

Q’ab aitan pot revenir

Mos cors, quez es envejos

De vos mout e cobeitos.

Amics no m laissatz morir

Pueis de vos no m poso gandir,

Un bel semblan que m revegna

Faiz, que m’aucira’l consir.

I care not to feel

As I don’t believe he is pleased by me

He who has never observed

My good words nor my songs

Nor is there a good song

That tells me to go on without him;

I am afraid I will die

As he lives with another woman

And for me won’t leave her.

I will leave him; he insults me,

To death I am brought by worry

And since he does not retrieve me

He could at least observe

With light replies

To keep my heart in joy.

And his lady should not care

If I agitate him

Because I don’t ask him to stop

Loving nor serving her.

Let him serve her; but to me return

As to not let me completely die;

I am afraid of the strength of

His love that makes me languish.

O! Friend valiant and good,

Because you are the best that ever was,

Don’t try to make me turn from you:

But you still don’t want to do or say

What I need to hear to stop

Loving you and giving you grace.Thank you, what may come,

For all my suffering and pain;

And no knights should think

On me; for I do not desire it.

Fair friend, I greatly want you

On you I embed my eyes;

And it pleases me at you to look,

Since as fair as you there is no other.

To God I pray to hold you in my arms;

No other can be enough.

I will be rich, if I can know

How to find a place

Where we can kiss and embrace;

With this it is enough to revive

My heart, that you made wanting

For you and most greedy.

Friend don’t let me die

Because I cannot win from you

A fair smile that can revive me

And ameliorate my worry.

Regardless of the disputed status of this work, whether Castelloza composed it or not I think it can be agreed that it is nevertheless a beautiful piece worthy of analysis. Thus without broaching the issue of its origin for now, I want to focus on it as I had done in previous works, piecemeal.

While keeping in line with what may be referred to as traditional trobairitz canso material, or at least form, here the ennobling love is clearly absent. She does not look towards her lover as a means towards spirituality, where by loving him she straddles a realm between humility and divine devotion, both of which lead to a plane of higher existence. She is not exalted by her love for him. She is not justifying her love for one who is not her husband by explaining away the purity of her love. While she maintains a brief facade of undying, and undeserving love for him, here she sings of nothing deeper than lust.

Initially this may appear as a debasement of courtly love, or a degeneration of fin’amor which is supposedly the driving force behind her work. However, in recalling my reaction to and interpretation of fin’amor in a previous section, the concept is faulty from the onset. This song does not in fact detract from the tradition, but rather enriches it by adding yet another layer to the definition of love the audience has thus far been privy to – the human, and very much physical aspect of it.

She may well die on the streets of Southern France for the unrequited love of a man who’s cruelty is without equal, and who does not deign to acknowledge her existence, but even as she extols her continuous selfless love for him, she is not so naive as to negate her other needs or desires. Nor does she believe them to be mutually exclusive. And I am fairly certain her audience would not make the same mistake either.

Platonic romantic love is an unsustainable paradox, and consequently precisely what would be inferred from her words if lust, or physical desire, was to be completely removed from the equation. However, while lust in itself does not belong to a higher order of love, in combination with deeper love it is not an anomaly.

If Castelloza wrote this (and I am trying very hard to refrain from touching upon that question here), then she has amply demonstrated every facet of love, leaving plenty of room for even the more unsavory kind that is reliant upon the deceit of another, who in this case are her husband and the lover’s other women. If Castelloza didn’t write this, then the woman who did enters a tradition where various forms of love have already been dissected in song, and thus she is free to explore myriad avenues love crosses – even this. Regardless, the trobairitz composing this makes clear she is not searching for a soulmate as much as an amorous encounter “on eu vos bais eus estregna” (where we can kiss and embrace), even if, as she states earlier, she does not mind his serving and loving his lady as long as she gets some of his attention. In other words, she understand her predicament at having lost his affection, and in her abysmal condition will settle for the proverbial breadcrumbs. Or so it seems.

As I argued that the trobairitz invert the male/female dynamic found within general troubadour poetry, so do they play with the accepted concepts to create a voice outside that which is expected. Here, the singer’s voice is not a monotone insync with feeling that is reliant upon pleas and bargains. There is a certain self awareness and rawness in her words that cannot escape a closer inspection. As she instructs that “ja a sidons nu tir” (his lady should not care) about her existence she is candidly stating what we shall hear again a hundred years later in the mouth of the Wife of Bath: “He is to greet a nigard that wol werne / A man to light a candle at his lanterne; / He shal have never the lasse light, pardee (lines 333-335). In short, she does not skirt the issue, nor is her song an endless pit of pity – she approaches the situation fully aware, conceding her unending love, whether for convention’s sake or not, and makes evident her stance.

In the end, this is not a woman on her knees, but rather storming upon her lover, informing him or her presence (which he could not have possibly by now missed). Further, while she writes this she understands it serves a greater purpose – entertainment – and as such, she caters her words to the proper format while using her audience as a means of publicly calling out her lover for his neglect.

While those who hear her song fear for her sudden loss of life in the face of love, due to the earthly qualities of her malheur they sympathize with her. She is not a divine embodiment of female perfection, nor is she the slightly inverted prototype for Laura. She is a woman, scorned, in pain, frustrated, in love, in lust, confused, and singing about it.

(Close up from above picture)

Sources:

Akehurst,F R P, and Judith M Davis. A Handbook of the Troubadours.

Bruckner,Matilda Tomaryn. “Fictions of the Female Voice: The Women Troubadours.”

Huchet, Jean-Charles. “Les femmes troubadours ou la voix critique.”

Mahn, A. Der Troubadours In Provenzalischer Sprache.

Wilson, Katherina. Medieval Women Writers.