(Agony in the Garden. Drawing from the Abbey of St. Walburg, Eichstatt, ca. 1500)

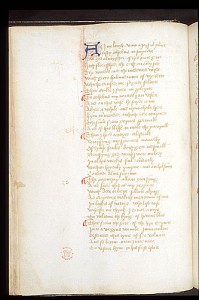

A few weeks ago I introduced Lydgate’s “As A Mydsomer Rose” with some concepts/techniques and a discussion of the poem’s mechanics. Here I want to get into the actual poem and look at some of the language he used.

The poem begins easily enough with an attribution of all human qualities to God, meaning we cannot take credit or feel pride for qualities we are not responsible for.

Lat no man booste of konnyg nor vertu,

Of tresour, richesse, nor of sapience,

Of worly support – al comyth of Ihesu:

Counsayl, confort, discresioun, prudence,

Prouisioun, forsight, and providence,

Like as the Lord of grace list dispoose:

Som hath wisdam, som hath elloquence,

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roose.

As is apparent from the last line of the first stanza (a motif that will be carried throughout), nothing is permanent – like a mydsomer rose everything changes, degenerates, withers, and dies. Yet this is not a new concept; poets from classical times to Lydgate’s contemporaries used the rose as a symbol of ephemeral beauty (such as the Roman de la Rose). Alain de Lille explored the motif throughout his Latin poetry (in which roses were often a central image). And Lydgate himself played with the image and even this exact refrain throughout some of his other works.

Holsom in smellying be the soote flourys,

Ful delitable outward to the sight,

The thorn is sharp curyd with fressh colourys.

Al is nat gold that outward shewith bright.

A stokfyssh boon in dirknesse yevith a light,

Twen fair and foul, as God list dispoose,

A difference atwix day and night:

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roose.

I believe this stanza to be pretty self explanatory where outward beauty, or physical perceptions like those of scent, can contradict and even camouflage the “thorn” underneath. This is directly addressed in the fourth line of the stanza (with an explicit reference to Alain de Lille), and indirectly alluded to in the fifth where a “stokfyssh boon” or the bone of a type of fish similar to cod represents a dichotomy between what is, and what appears, since this type of fish is generally split in half with the bone delineating its two sides. This same imagery carries over to the next lines where the difference is compared to that of day and night with a secondary allusion to day as associated with light and purity and night with darkness and all things “foul.”

Floures open vpon euery grene,

Whan the larke, messager of day,

Salueth [th]’uprist of the sonne shene

Moost amerously in Apryl and in May;

And Aurora ageyn the morwe gray

Causith the daysye hir crown to vncloose:

Wordly gladnes is medlyd with affray,

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roose.

Here the imagery is of rebirth and rejuvenation where each image is of a thing at its most viral point in life and full of promise: flowers opening, dawn beginning the day, the lark welcoming the morning. But with these images comes the realization of an end where dawn turns to dusk, birds go to sleep, and flowers close. Here the juxtaposition is a bit more subtle as the organic sense of this scene allows for the possibility of reincarnation as opposed to absolute death – at least briefly. So the mydsomer rose, the portent of death, functions in direct opposition to “Aurora” and the “larke,” who will rise again tomorrow.

Atwen the cokkow and the nightyngale

Ther is a maner straunge difference.

On frssh baunchys syngith the woode wale.

Iayes in mysyk haue smal experyence.

Chateryng pyes whan they come in presence

Moost malapert ther verdite to purpoose:

Al thyng hath favour, breffly in sentence,

Of soffte or sharp like a mydsomyr roose.

The imagery of night and day is carried over to the first line of this stanza as depicted by the cuckoo (a diurnal bird) and the nightingale (an obviously nocturnal bird). However, another allusion is to the popular song “Sumer is icumen in” where we are bid to sing “cuccu” to welcome the season. While this is a merry song, the mention of the nightingale draws attention to yet another reference – “The Owl and the Nightingale” – in which the two attempt to solve their debate, or as Lydgate states, their “verdite” to no avail as here “al thyng hath favour,” but we must remember, only “breffly” because all things change, like a “mydsomer rose.”

The roial lioun lette calle a parlement,

Alle beests abowt hym enviroun,

The wolff of malys, beyng ther present,

Vpon the lamb compleyned, ageyn resoun,

Said he maad his watir vnholsom,

His tender stomak to hyndre and vndespoose:

Raveynours reign, the innocent is bore doun,

Al stant on chaung lyk a mydsomer roose.

The first thing that came to mind when reading this stanza was the distinction between a parliament of animals and that of a parliament of birds (Chaucer). Granted, the reasoning for holding a congregation is different, the idea is quite interesting. Apparently the wolf’s complaint agains the lamb is not unique, but the concept of a parliament to address the issue is. Then I found another similar instance in Lydgate’s “Debate of the Horse, Goose and Sheep.” Although this all seems very fable-like, according to MacCracken, Lydgate may have been the originator of this concept since it is not in fact a part of the fable tradition.

Al worly thyng braydeth vpon tyme:

The sonne chaungith, so doth the pale moone,

The aureat noumbre in kalends set for prime.

Fortune is double, doth favour for no boone,

And who that hath with that queen to doone

Contrariously she wyl his chaunce disppose:

Who sittith hihest moost like to fall soone.

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roose.

This stanza directly addresses the passing of time and the changes which come with it, especially focusing on the fickle nature of fortune as she weaves in and out of a person’s life as she sees fit – again, not a new concept, and was probably inspired by Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy which served as an inspiration to many different medieval authors. However, the most fascinating part of this stanza is the language used, denoting a familiarity with calendars, specifically perpetual liturgical ones. It has been argued that “kalends” in this instance is the first such use of the word to refer to a calendar. I don’t know if I agree. The “aureat noumbre” refers to the number of the lunar cycle by which the date of Easter is calculated. “Prime” is a sequence of numbers ranging from 1 to 19, applied to various days, and it is the golden number, used for locating the age of the moon on a given date. “Kalends,” when reading a perpetual calendar, is the first of the month. So what is literally being stated is that Easter happened on April 1st, which in 1432 it did, coincidentally within the time frame that the poem is thought to have been written (currently narrowed down between 1431 and 1440). While this may have been the first instance of “kalends” being used in a metonymical sense to represent a calendar as a whole, I would go as far as suggesting it as a means of actually dating the poem to 1432.

The golden chaar of Phebus in the ayr

Chasith mysts blak that [th]ay dar not appeere,

At whos vprist mounteyns be made so fayr

As they were newly gilt with his beemys cleere;

the nyht doth folwe, appallith al his cheere

Whan western wawes his streemys ouer-close.

Rekne al bewte, al fresshness that is heere:

Al stant on chaung lyke a mydsomyr roose.

This is a very straight forward representation that once again picks up on the idea of the setting sun as an exemplum of change where the sun functions as the connecting point between the first and second half of the stanza, as both halves tie in with the change of the mydsomer rose. While the language here is quite beautiful what I find even more interesting is the variation between manuscripts which is the most pronounced in this stanza. The stanza seen here (that follows the B tradition) is completely altered from the A variation (with a bit more of a discussion about that here).

Constreynt of coold makith flours dare

With wynter froosts that they dar nat appeere.

Al clad in russet the soyl of greene is bare.

Tellus and Ioue be dullyd of ther cheere

By revolucioun and turnyng of the yeere:

As gery March his stoundys doth disclose:

Now reyn, now storm, now Phebus bright and cleere.

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roose.

Once again we encounter ideas or phrases that originated in earlier works and others that will reemerge in later ones. This stanza brings to mind Chaucerian language from Troilus, while serving as an early reflection for the Fall of Princes. The ubi sunt motif that is going to begin in earnest in the next stanza is already beginning to take shape as the whereabouts and transience of various entities is being addressed.

Wher is now Dauid, moost worthy kyng

Of al Iuda, moost famous and notable?

Wher is Salomon most soureyn of konnyng,

richest of bildyng, of trsour incomparable?

Face of Absolon, moost fair, moost amyable?

Rekne vp echon, of trouthe make no gloose,

Rekne vp Ionathas, of frenship immutable,

Al stant on chaung lyke a mydsomyr roose.

Wher is Iulius, poudest in his empyre

With his tryumphes moost imperyal?

Wher is Pirrus that waws lord and sire

Of al Ynde in his estat roial?

And wher is Alisunder that conqueryd al,

Failed leiser his testament to dispoose?

Nabugodonosor or Sardanapal?

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roose.

Wher is Tullius with his sugryd tonge?

Or Crisistomus with his golden mouth?

The aureat ditees that be red and songe

Of Omerus in Greece both north and south?

The tragedyes diuers and vnkouth

Of moral Senek, the mysterys to vncloose?

By many example this matere is ful kouth:

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roose.

Wher been of Fraunce al the dozepeers

Which [th]at in Gawle had the governaunce?

Vowes of the Pecok with al ther proude cheers?

The worthy nyne with al ther hih bobbaunce?

Troian knyhtis, grettest of alliaunce?

The flees of gold, conqueryd in Colchoos?

Rome and Cartage, moost souereyn of puissaunce?

Al stant on chaung like a mydsomyr roos.

At this point the catalog of names in the motif is part of convention – the various figures only serve to remind the reader of their likeness to the mydsomer rose. There are also buried within the line numerous allusions to earlier or even contemporary works with which Lydgate’s audience would have been familiar. Further, he once again self-references, in an almost cryptic manner that relies on knowledge of his previous works for understanding. For example, “the worthy nyne” is a direct mention to his “That now is Hay Some-tyme was Grace” where the nine are actually named (note: most of the online versions you will find do not include the entirety of the poem, only focusing on the “catchy” refrain.” There is *a lot* more to it). However, this last reference is most appropriate since these two poems are considered sister poems written for Queen Kateryn. Without delving too deeply into the second poem, mortality is the central and unifying concept between the two.

Put in a som al marcial policye,

Compleet in Affryk and boundys of Cartage,

The Theban legioun, example of cheualrye,

At Rodanus Ryuer was expert ther corage:

Ten thousand knyhtes born of hih parage

Ther martirdam, rad in metre and proose,

Ther golden crownys maad in heuenly stage,

Fressher than lilies or ony somyr roose.

Here the imagery becomes more clear as he sets up the martyrdom of the rose, completing the imagery of the rose as the epitome of mortality. First, a quick note on his “Theban legioun” that alludes to the Fall of Princes. Here the “legioun” is a symbol of martyrdom further perpetuated on the “stage” that is the martyr’s scaffold. This “legioun” historically refused to pledge to pagan gods through sacrifice as described in Jacobus ad Voragine’s Legenda Aurea.

The remembraunce of euery famous knyht

Ground considerid, is bilt on rihtwisnesse.

Race out ech quarel that is not bilt on rigt,

Withoute trouth what vaileth hih noblesse?

[Th]’awtiers of martirs foundid on hoolynesse:

Whit was maad red ther tryumphes to discloose:

The whit lillye was ther chasst clennesse,

Ther bloody suffraunce was no somyr roose.

It was the Roose of the bloody feeld,

Roose of Iericho that greuh in Beedlem:

The five Roosys portrayed in the sheeld,

Splayed in teh baneer at Ierusalem.

The sonne was clips and dirk in euery rem

Whan Christ Ihesu five wellys lyst vncloose

Toward Paradys, callyd the rede strem,

Of whos five woundys prent in your hert a roos.

Floral imagery was an extremely familiar means of describing both Mary and Christ in the Middle Ages (lilies and roses being very prominent forms), just as the comparison of Christ’s wounds with roses was commonplace. By this point in the poem the rose should immediately signal the juxtaposition between the ephemeral and the heavenly. I think these last stanzas really capture the physicality of Christ, and paradoxically emphasize his transcendence by focusing on his flesh. Here the image of the rose and Christ’s five wounds become superimposed as the iconography shifts to that of a single five-petalled rose. Personally when reading this the first thing which cropped into my mind was Gawain’s shield that remained within focus throughout the story, expanding towards infinity through the catalog of fives that ascended from the trivial to the eternal.

Thus the rose moves from the image of fleeting worldly beauty in the first stanzas, to a more substantial query into mortality and the meaning of life, to finally taking the place of the symbols of eternal salvation, and consequently serving as a reminder of what it means to be human.

Sources:

Bale, Anthony. “Twenty-First Century Lydgate.”

Bezella-Bond, Karen. “Blood and Roses.”

Ebin, Lois A. John Lydgate.

Grossi, Joseph. ”’Wher ioye is ay lastyng’: John Lydgate’s Contemptus Mundi in British Library MS Harley 2255″

McCracken, Henry Noble. The Lydgate Canon.

—. Minor Poems of John Lydgate.

Pearsall, Derek. John Lydgate.

Scanlon, Larry, and James Simpson, eds. John Lydgate: Poetry, Culture, and Lancastrian England.