If art recreates life, than Francois Villon’s life provided plenty of fodder for his art. His existence, albeit for the most part unsavory, infused his poetry with an intensity that elided artifice. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his ballad “L’Epitaphe” that he wrote while awaiting his death sentence by hanging all the while looking out of his cell window at those who were previously hung.

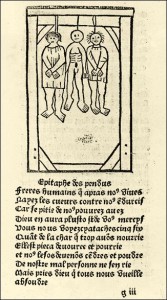

(Opening of “L’Eptiaphe” from the first dated edition of Villon’s works, published by Pierre Levet in 1489 – Reserves des Imprimes, Bibliotheque Nationale)

Villon was born Francois de Montcorbier, but adopted the surname of Guillaume Villon, his childhood caregiver. He began his ascent into society well enough having reached the University of Paris and obtained a Master of Arts by 1452, only to take a turn for the worst beginning with a brawl in 1455 where he killed a priest (which some testified was self defense). He was pardoned only to find himself on the opposing side of the law later in the same year after being implicated in the robbery of a large sum of money from the Faculty of Theology. Following a few years of more or less vagabonding (with stints at the courts of Charles D’Orleans at Blois and Jean II, Duke of Bourbon at Moulins), he was imprisoned again. This time his savior was Louis XI, whose visit to the region of Meung-sur Loire, where Villon was imprisoned, prompted a dispersal of amnesties from which Villon benefited.

Less than a year later Villon was imprisoned for the last time, and sentenced to hang. This is the point when most believe he composed “L’Epitaphe,” while awaiting his punishment, unbeknownst to him that his sentenced would be commuted to exile from Paris. He followed these orders and little to nothing is known of his life after this point.

However, despite living through the ordeal, the immediacy of the poem at the moment where his life was about to be taken away is not altered. Before going further, here is the poem, along with my translation:

Frères humains, qui après nous vivez,

N’ayez les cœurs contre nous endurcis,

Car, si pitié de nous pauvres avez,

Dieu en aura plus tôt de vous mercis.

Vous nous voyez ci attachés, cinq, six:

Quant à la chair, que trop avons nourrie,

Elle est piéça dévorée et pourrie,

Et nous, les os, devenons cendre et poudre.

De notre mal personne ne s’en rie;

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre!

Si frères vous clamons, pas n’en devez

Avoir dédain, quoique fûmes occis

Par justice. Toutefois, vous savez

Que tous hommes n’ont pas bon sens rassis.

Excusez-nous, puisque sommes transis,

Envers le fils de la Vierge Marie,

Que sa grâce ne soit pour nous tarie,

Nous préservant de l’infernale foudre.

Nous sommes morts, âme ne nous harie,

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre!

La pluie nous a débués et lavés,

Et le soleil desséchés et noircis.

Pies, corbeaux nous ont les yeux cavés,

Et arraché la barbe et les sourcils.

Jamais nul temps nous ne sommes assis

Puis çà, puis là, comme le vent varie,

A son plaisir sans cesser nous charrie,

Plus becquetés d’oiseaux que dés à coudre.

Ne soyez donc de notre confrérie;

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre!

Prince Jésus, qui sur tous a maistrie,

Garde qu’Enfer n’ait de nous seigneurie:

A lui n’ayons que faire ne que soudre.

Hommes, ici n’a point de moquerie;

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre!

Our human brothers, who live after us,

Don’t against us harden your hearts,

For, if pity on us poor ones you take,

God on you will have sooner mercy.

You see us here hanging five, six:

Of our flesh, that we have well nourished,

It has been devoured and rotted,

And us, the bones, are becoming ashes and dust.

Of our misfortunes do no laugh,

But pray God that he may absolve all of us!

If brothers we call you, do not become

Disdainful, even though we are killed

For justice. Each time, you know

That not all men have good sense;

Pardon us, for we are transitioned

Towards the son of the Virgin Mary,

That his grace for us not dry up,

But us preserve from the infernal lightning

We are dead, let no soul us trouble;

But pray God that he may absolve all of us!

The rain us has steamed and washed,

And the sun dried and blackened;

Magpies, crows, our eyes have gouged,

And pulled out our beards and eyebrows.

Never, at no time, at rest are we;

Now here, now there, how the wind changes;

At its pleasure it us carries,

More pecked from birds than a thimble.

Thus do not be of our brotherhood,

But pray God that he may absolve all of us!

Prince Jesus, who of all is master,

Guard that Hell doesn’t over us have lordship:

To it we have nothing to do or to make,

Men, here there is no mockery,

But pray God that he may absolve all of us!

This is a straight forward ballad which includes three stanzas, each consisting of ten lines with ten syllables each, and a brief envoi, all using the same rhymes, and each stanza ends with the same line. Unlike the English ballad that is best suited for more joyous occasions (with a few exceptions), and often accompanied by a song, the French ballad is far more somber. Here however, the form is far overshadowed by the content.

Life and death are the central themes, from the title that denotes an inscription on a tombstone, to the juxtaposition between those who will remain alive and those who have already hung, amongst whom the poet counts himself.

As he begins by beseeching his audience to have pity, his lines act as a memento mori, reminding his audience that they too will die even if not by being hanged as convicts. Further, in the end, it is only the soul that survives and repentance saves all regardless of what may have been while the soul lived among “de la chair,” (the flesh).

The imagery of salvation and the afterlife directly opposes the carnally grotesque and disfigured bodies that hang rotten and devoured, which is further made obvious by giving the corpses a voice. In death they are vocal and retain the potential for salvation, even as the living whom they address remain muted at the sight of the decaying bodies, silently judging their crimes, practically oblivious to their own impending deaths. Through their refusal to speak, to pray for the corpses as the speaker wills them to do, they negate their own salvation because as they pray, God will not only save those for whom they pray, but “tous nous,” all of us.

Thus Villon not only throws in his lot with the convicted men hanging outside his window, but through his constant use of “nous,” us, and his reoccurring refrain for each stanza, “mais priez Dieu que tous nous vueille absouldre!” he becomes the spokesman for mankind, using his last words as a universal warning for all to repent, so that God “may absolve all of us.”

Sources:

De Vere Stacpoole, Henry. Francois Villon: His Life and Times, 1431-1463.

Fox, John. The Poetry of Villon.

Peckham, Robert. Francois Villon: A Bibliography.

Siciliano,Italo. Francois Villon et les themes poetiques du moyen- age.