This isn’t really a post, but rather a rough sketch as I gather my ideas for the PCA/ACA conference in April where I will be presenting on the Crusades, and specifically their representation in modern pop culture. Before getting started, here is the abstract I originally submitted that the conference accepted:

The popular video game, Assassin’s Creed, is a modernized and highly embellished built upon version of the feud between the medieval Assassins of the east the the Crusaders of the west. However, what is most noteworthy about the premise is the context in which it is used. The Crusades, ubiquitously associated with Western culture and Christianity become inverted within the video game as the players (typically westerners) take on the role of the Assassins, literally placing themselves in the role of the “other.” Large portions of the game take place in medieval milieus, notably Masyaf in Syria, a land that has had great global consequence today. This paper would like to argue that through the violence in the video game’s premise, it brokers pacifism, understanding, and tolerance.

Arguably the road towards pacifism is not a conscious undertaking the players participate in, but it nevertheless opens the line of communication between the past and present. Moreover, it familiarizes the general population with these past events, cultivating a curiosity for further research into the history behind the video game as is made apparent by the numerous websites which have sprouted up in recent years that are dedicated to separating out fact from fiction within the plot.

The medieval conflict between the Knights and Assassins in Assassin’s Creed is sufficiently distanced from the modern period to allow dissociation while nevertheless providing the impetus necessary to learn about points in history that have shaped our culture today from the perspective of another.

The video game, now a massive consumer fueled chain, focuses on three different time periods. I wont’ go into too much detail, and you can view specifics about the game here, but briefly, since I only have fifteen minutes, I will be focusing on the earliest of the time periods depicted, the twelfth century during the Third Crusade. First, the name is an arbitrary distinction – an attempt historians have made to differentiate between the various expeditions, often ignoring the various smaller skirmishes and battles taking place in between the larger endeavors. However, I too will focus on what is traditionally considered the Third Crusade, if only to narrow my research, and also to align my findings with the depictions found within Assassin’s Creed.

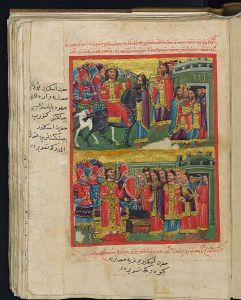

(Philip Augustus arriving in Palestine, Royal 16GVI f. 350v)

(Battle of Arsuf, September 7, 1191)

(Assassin’s Creed screenshot of what is supposed to be the same time period as the two above)

The historiography for the period is incredibly problematic due to the high concentration of points of view associated with the Crusades. In other words, this is not a simple “us versus them” issue where you either look at it from the Christian perspective or from that of the Saracens. Within each group there are several denominations, nationalities, and interests – not everyone was in it for spirituality, and neither sides were as unified or hostile as it may have initially appeared.

In 1095 Pope Urban II, at the Council of Clermont, launched the Crusades in an attempt to capture the Holy Land, Jerusalem. Of course travels to the Holy Land did not begin with the Crusades, and pilgrimages to Jerusalem had been documented for hundreds of years, but the political climate in the eleventh century was ripe for attempts at conquering the land in the name of the Holy Roman Church. What began as a quest for absolution from sin as Urban promised that “all who die by the way, whether by land or by sea, or in battle against the pagans, shall have immediate remission of sins” (Gesta Francorum Jerusalem Expugnantium, Fulcher of Chartres), eternal glory, and ultimately a deeper connection with Christ ended in bloody battles and terror, with Jerusalem remaining ultimately unclaimed. Yet this First Crusade paved the way for future attempts through its success at obtaining some land (parts of Jerusalem, Edessa, Antioch, and Tripoli), temples, and strongholds that would later benefit the west. With the incoming of westerners to the Eastern front, many who boasted significant wealth, the local economy improved, evident from the numerous artisans and tradesmen who migrated to the areas where palace strongholds were being erected.

More research is needed, but it seems to me that the different Crusades were depicted as episodic due to the various times of peace, and each new expedition brought a resurrection of previous Crusade sentiments, along with an upheaval to the more or less functional settlements. According to the chronicles of Fulcher of Chartres, it appears that in between the First and Second Crusades westerners were assimilating into Eastern culture and adapting their lifestyle.

(Here Byzantine emperor Nicephorus III receives a book of sermons from Saint John Chrysostom who was an archbishop of Constantinople in the mid fourth century and an important figure of the early church, and Saint Michael, depicting the mingling of cultures – BnF MS Coislin 79 folio 2v, circa 1075)

(Another conflation of cultures and times periods where Alexander the Great is depicted as a Byzantine Emperor and his troops are costumed like Byzantines as they receive Jewish rabbis – Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodl. 264).

I am not yet entirely sure where I am going with this, but what is becoming more apparent the longer I research is that my findings, as I approach the time period I am most interested in, frequently refer to the Second Crusade as a complete failure, which brings to question from whose perspective these accounts are forged. Yes, from the Christian perspective, and certainly that of the Church, this specific Crusade was an abysmal failure where land was lost, much money was spent, and little results returned, but when regarded from a Saracen perspective, the westerners were successfully pushed back, land was reclaimed, and crises were averted. How then are the Crusades categorized? Nevertheless, I am hesitant to simplify these opposing viewpoints as merely two sides of a coin, and believe there were nuanced, disparate histories simultaneously operating where there is no clear winner or loser. Further, returning to my goal for this research, in attempting to situate the game, Assassin’s Creed, in the midst of this, most western accounts must be discounted as biased, and instead the focus must rely on Saracen encounters with the perceived enemy. After all, the violent video game depends on an antagonistic perception of the volatile Knight Templar attempting to eradicate eastern heritage and steal holy land.

Before continuing any further with this I think I need to better understand how these discordant ideas can become harmonized to create a more holistic image of the Crusades. In short, how do the Crusades, from a Saracen aspect, fit into Western ideology in order to allow the game to portray it as such?

Sources:

Fulcher of Chartres, A History of the Expedition to Jerusalem, 1095-1127, trans. Francis Rita Ryan, ed. Harold S. Fink

Hamilton, Bernard. Monastic Reform, Catharism, and the Crusades.

Hillenbrandt, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives.

Paul, Nicholas, and Suzanne Yeager, eds. Remembering the Crusades: Myth, Image, and Identity.