During the middle of the eleventh century the Gregorian Reforms were introduced as a method of expunging certain less than pious practices from the clergy. However, the reforms carried other consequences that extended into the laity, a portion of the population that included even the ranks of religious women from nuns to abbesses. While the Church was always a male oriented institution, before the reforms female members also benefitted – it was a locus of education, and provided women with a certain amount of freedom and safety unknown in the secular world. With the reform women were systematically stripped of their roles within the church, and mixed, or dual monasteries became a thing of the past, further depriving women of venues for learning, scriptoriums, substantial libraries, or even opportunities for collaboration.

(Cistercian Nuns – British Library, Yates Thompson MS 11 f. 6v)

However, the coup de grace to women’s intellectual growth was the prohibition of magisterium vocis, public preaching, which was previously an activity that afforded women the opportunity to read, interpret, and explore scripture on a larger scale. With this ability taken away from them, nunneries no longer provided many of the same benefits to society as they were once able to, and thus many patrons began withdrawing their support, preferring instead to share their wealth with monasteries that could provide services. Ironically, this type of lay intervention from the nobility and upper class was precisely what the Gregorian Reforms set out to eradicate. Yet the power of monetary intervention cannot be overstated as it was often the guiding principle behind many of the decisions these religious houses made. Consequently from the loss of power stemmed the loss o money, and the one act of removing preaching for public welfare from these venues became the agent for rapid and lengthy decline.

So, preaching was a means for women to participate in monastic life, discourse, and education, but perhaps most importantly, it gave them a voice.

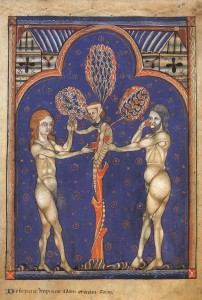

Yet, this voice was heard and interpreted with various degrees of apprehension and trepidation. Without hinging upon an absolute argument that posits all women as wicked, seeing as how there were women who were respected and revered for their minds and devotion, and who wielded significant power, there was nevertheless a broad acceptance of the Mary-Eve separation. As the cult of Mary was rising during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, so was her comparison to the first female figure, Eve. Needless to say this comparison that situated the majority of women far closer to Eve than they could ever be to Mary, rendered an image of woman as temptress, weak spirited and even dull witted.

(to further emphasize woman’s role in man’s fall, the serpent in this well known depiction of Adam and Eve has a feminine head – St. John’s College MS k. 26 f. 231)

Thus women navigated a rather tricky plane as they elided a fixed categorization. Even within the church multiple debates arose in regards to what their function should be, and to what extent they could practice their calling. As restrictions further increased, “when a teaching or preaching woman [was] encountered in twelfth and thirteenth century medieval sources her ability to speak about divine matters [was] generally attributed to a charism of prophecy rather than to intelligence” (Muessig 147). In the few instances when women attempted activities relatively close to preaching and were successful in their endeavors, they were immediately relegated to categories of divinity, as their voices bore supernatural gifts. Of course the implication of “supernatural” is also “unnatural,” since the rationale needed for expounding on the meaning of scripture was not reserved for women. Even as education improved, female abilities according to male patrons continued to rely on notions of divine inspiration, and various forms of preaching became understood as prophecy to be written and interpreted by hagiographers such as in Vita Sanctae Hildegardis. In other words, as Thomas of Chobham stated, women could deliver moral lessons, but not explain their meaning in the traditional sense of preaching. Highly literate women were no more than mouth pieces to read scripture, refraining from any commentary, practicing the silence and obedience that was expected of them.

(Vita Sanctae Hildegardis Plate 197 – Hildegard receiving a vision which echos a previous plate from her Scivias)

(Hildegard receiving a vision – Frontpiece of Scivias)

If formal preaching was not allowed, and women could not overtly explicated scripture, other mediums offered the necessary avenues for alternate mechanisms of preaching. While some women, such as Hildegard von Bingen, embraced their status as prophetesses and used it to articulate their religious beliefs, Hildegard, too, found alternate routes of expression. Entertainment became an increasingly thriving method for the task, allowing moral lessons to be performed through various means. Two well documented cases of women enlisting the arts in order to preach come from thirteenth century France: Marie d’Oignies and Christina of St. Trond. While both used song as their choice channels of communication, as did Hildegard at one point, preaching was not always practiced orally, even when in an artistic format, as can be seen through the various morality plays and stories told, including the Ordo Virtutum which was perhaps the first of its kind.

Here is a brief modern interpretation of Hildegard’s “O virga ac diadema” for your musical enjoyment:

And another snippet from the Ordo Virtutum:

Despite the ever more confining world these women found themselves in, it was through creativity and resourcefulness that that they found their voices – in song, poetry, and as is of particular interest to me for a larger project, reshaping of narrative.

Sources:

Kienzle, Beverly Mayne. “Sermons and Preaching.”

King, Margot H. Two Lives of Marie d’Oignies: The life of Jacques de Vitry.

Mooney, Catherine M. “Authority and Inspiration in the Vitae and Sermons of Humility of Faenza.”

Muessig, Carolyn. “Prophecy and Song: Teaching and Preaching by Medieval Women.”

Silvas, Anna. Trans. Jutta and Hildegard: The Biographical Sources.

Thomas of Chobham. Summa de arte praedicandi. Ed. Franco Morenzoni.