On one of my previous posts a Twitter discussions started where we began wondering whether Troubadour poetry about women was really written by women, or if the females simply performed words created by men. I am hesitant to believe one or the other and felt there was probably a mixture of authentic female voices, and those that only mimicked feminine sentiments. Despite numerous sources that referred to these poets as female, I remained skeptical as no actual proof was offered, and it appeared that the subject matter of the poems (women’s lives) informed the way the anonymous poets were regarded. Simply because feminine plight was at the center of these works did not absolutely point to a female writer, which should have been immediately apparent from one of the poems I translated by Clement Maron, “Of the Young Lady With An Old Husband,” that was clearly written by a man.

Per usual this lead to further research. Where did women stand within the Troubadour tradition? As it turns out, right in the center, playing a rather prominent role in not just reciting, but creating many of the works that have come down to us today.

(“Flower Dance” – Ermengol, Breviaire d’Amour, 12th century, Bibliotheque Royale, Escurial)

(British Library, MS Royal 16 G. V folio 3v)

During the High Middle Ages Troubadours were composers and performers of lyric poetry. Initially this form of art was prevalent in the Occitan, but then by the thirteenth century migrated to Italy and Spain. Trobairitz are female Troubadours, however this term came about late in Troubadour history, the thirteen century, and was not widely circulated. Thus most Troubadours, regardless of their sex, used the same identifier, rendering their works in many cases indistinguishable. If only writings by Trobairitz were considered female, their contribution to poetry would appear painfully barren.

Yet, this term, I think, serves another interesting purpose. I see it as a defined distinction between men and women within the Troubadour tradition, as well as delineating the same difference for us today. It is easier to generalize the term and refer to all female Troubadours as Trobairitz, which for my purposes here I will use. However, most importantly, it shows there was a need even in the Middle Ages to distinguish between the two genders when regarding their works.

(Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale MS Francais 599 folio 19)

Authorship hardly had the same meaning as it does for us today, but it appears voice was the discerning factor. Troubadour and Trobairitz poems were highly stylized which makes it difficult to argue the precise point where the authentic female voice is found, but when looking at the subjects that were typically touched on by both sexes, voice becomes very important. Courtly love, and specifically fin’ amor, a favorite of the Troubadours, parades under the guise of exulted love and reverence for the female while simultaneously encapsulating her within male ideals. This poetry was not only stylized in form, but also in content, and the female form, albeit adored, was also severally restricted.

While I am sure some women did simply mimic the men who in turn mimicked them, in some sort of thrice removed poetic rendition of love, I also believe that within the confines of this tradition women were not simply slaves to the expectations of the system, but participants in their own right, altering the pieces to better reflect their own opinions.

It has been stated that the female Troubadours, or the Trobairitz, were more realistic in their assessment of love, but I think this stemmed from a better understanding of self. If Troubadour poetry set out to idolize the female, spiritually and physically, it would follow that a woman would be most in touch with herself and her own body, less enamored by some abstract ideal that she knows to be absolutely impossible.

I would like to challenge the notion of fin’amor as an ideal love and posit it where it belongs, among men. The creation of a female ideal to be risen atop a pedestal is the medieval equivalent of modern day concepts of beauty that glorify a woman for unattainable spiritual and intellectual acumen. It was supposedly love that transcended all earthly quality, considered in line with Platonic ideals, all the while bridging the gap between lovers on a metaphysical plane. In other words, it did not celebrate women, but rather the way men wished women would be, and the qualities expressed in each song were reliant on a repertoire of topoi, further indicating the rigidity of the form and the constraints into which the subject, the woman, was placed.

Here would perhaps be an ideal place to get into the logistics of what becoming the subject of these songs meant, especially when looking at them in terms of Foucault and even more effectively, Althusser, where subjectivity and interpolation would become the living definition of these women. However, I am going to save this for perhaps a larger project, and rather jump into the female interpretation of this genre.

If it has not already, it should now become apparent that women writing these poems would be at a loss for inspiration. They understood their own shortcomings, and would not eagerly participate in idealizing their own. Thus when women spoke they had two options: to occupy the place of man and falsely attribute perfection to fellow woman, or to invert the roles and speak as women raising men onto the same pedestals. More often than not, they took the former approach in which women were further objectified by their own under the guise of pleading their cases, justifying their existence within the tradition. In other words, they acquiesced to the men’s charges of their perfection, and needed to find a means of validating them.

However, there were some that used the form for their own ends and poetry became the tool for systematically demolishing these false ideologies. However, as Audre Lorde has warned, the master’s tools can never be used to dismantle his house, only to disturb it temporarily. Even though the handful of Trobairitz did not overturn patriarchy (surprise!) they created enough of a disruption to, at the very least, draw attention to its conventions elucidating its modus operandi, and showing that these forms of expression were not what they appeared.

These small subversive acts were mainly conducted by appropriating the language of the Troubadours and using it to describe men in the same fashion they regarded women. Immediately it became apparent that there was a certain impossibility to the catalog of traits heaped upon these men, and the women’s voices sounded with the same deceitfulness as they had themselves encountered. Before this post gets too much longer, here is a sample of a surviving Trobairitz song by Beatritz de Dia – “A chantar m’er” – a song which has survived to today, and can still be replicated with its original chords (video below) as opposed to all the other poems that have since lost their accompanying melodies.

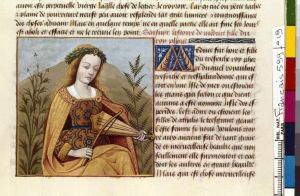

(Beatritz (Contessa) de Dia – Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale MS fr. 12473)

A chantar m’er de so qu’ieu non volria

Tant me cancur de lui cui sui amia,

Car ieu l’am mais que nuilla ren que sia;

Vas lui no.m val merces ni cortesia

Ni ma beltatz ni mos pretz ni mos sens,

C’atressi.m sui enganad’e trahia

Com degr’esser, s’ieu fos desavinens.

Meravill me com vostre cors s’orguoilla

Amics, vas me, per qu’ai razon qu’ieu.m duoilla

Non es ges dreitz c’autre’amors vos mi tuoilla

Per nuilla ren qe’us diga ni acuoilla;

E membre vos cals fo.l comenssamens

De nostre’amor! ja Dompnedieus non vuoilla

Qu’en ma colpa sia.l departimens.

Valer mi deu mos pretz e mos paratges

E ma beltatz e plus mos fis coratges,

Per qu’ieu vos man lai on es vostr’estatges

Esta chansson que me sia messatges:

Ieu vuoill saber, lo mieus bels amics gens,

Per que vos m’etz tant fers ni tant salvatges,

Non sai, si s’es orguoills o maltalens.

Mas aitan plus voill qu.us diga.l messatges

Qu’en trop d’orguoill ant gran dan maintas gens.

I must sing of that which I want not,

As I am angry with the one I love,

For I love him more than anything;

He cares not for mercy or courtliness

Not my beauty, nor my merit nor my good sense,

For I am deceived and betrayed

Exactly as I should be, if I were ugly.

I marvel at how proud you have become,

Friend, towards me, and thus I have reason to grieve.

It is not right that another lover take you from me

On account of anything said or granted to you.

And remember how it was at the beginning

Of our love! may the Lord God never wish

That my guilt be the cause of our separation.

My worth and my nobility,

My beauty and my faithful heart should help me;

That is why I send this song to your dwelling

This song that might be my messenger.

I want to know my fair and noble friend,

Why you are so cruel and harsh with me;

I don’t know if it is pride or ill will.

But I especially want the messenger to tell you

That many people suffer from too much pride.

(note: although I typically like to do my own translations, I have to admit this song was quite difficult in certain places, so here I have relied on the translation from Rosenberg et. al. but I have modified it where I thought it was appropriate – their translation is absolutely beautiful, whereas mine is more in line with my style that is mot a mot).

Two facets of this poem caught my attention. First, she loves him as she says, “more than anything,” meaning, more than is possible. He is proud and unkind, presumably having left her for another, yet she does not allow this to guide her decision of love. Despite his multiple faults, he is here seen as perfect, or as he should be, which is an echo of Troubadour poems that capture feminine ideal beauty despite that the subject may be far from fair.

Secondly, she is angry. Unrequited courtly love was supposed to garner silent, suffering patience. The courtly lover, playing his part, pined away endlessly without hope for even a glance from his love interest. He did not reproach her for her cold conduct. Here Beatritz, while lamenting her current state, conforming to the ritual of a weakened lover also overthrows these same notions, starkly pointing out how ridiculous silence and patience really are. He may be perfect, even if only in her eyes, but his knowledge of said perfection, and the ensuing pride, will be his downfall. Her song does not end with a promise of never ending affection, but with a warning.

This is but one example of a rich tradition that deserves much more exploration. Over the next few months I hope to uncover more and form deeper connections. Further, just like with my Female Scribe project that is still very much a work in progress, I want to situate this work in context with other pieces and other Trobairitz. Unfortunately the majority of these women individually are obscured, with some of the only knowledge we have of them coming from their vidas that have in most cases survived in tatters, and unlike vitas, are notoriously unreliable. However, even without absolute attribution of these works to various figures, I think this project holds great potential, so I suppose I will consider this Part I.

In the meantime, I leave you with the actual melody of the poem above:

Sources:

Bogin, Meg. The Female Troubadours.

Bruckner, Matilda T. “Fictions of the Female Voice: The Women Troubadours.”

Peraino, Judith. Giving Voice to Love: Song and Self Expression from the Troubadours to Guillaume de Machaut.

Rosenberg, Samuel, Margaret Switten, and Gerard Le Vot. Eds. Songs of the Troubadours and Trouveres: An Anthology of Poems and Melodies.

Shapiro, Marianne. “The Provencal Trobairitz and the Limits of Courtly Love.”