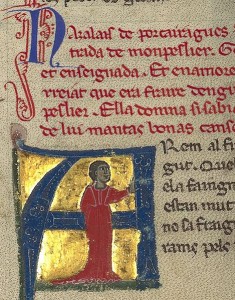

(Castelloza, BnF MS 843 f. 125)

I have been hesitant to continue my writing on the trobairitz not due to lack of interest, but in sheer awe of the corpus of works these women left behind which I have steadfastly been attempting to make my way through. While it is by no means an extensive collection, it is rich in a tradition that has remained ever so under examined. This is yet another post that humbly attempts to broach yet one more meager inch into understanding the trobairiz and what they meant to the even larger tradition of female writing.

What I find the most startling in their words is their candid tone that allows them to well overstep their social bounds and, through poetry, transgress. They do not adhere to their roles of subservience in their homes or in society, and their voices, as heard in their songs, are, for lack of a better term, saucy. The trobairitz etymologically are borne from the troubadours,those who find, and the trobairitz arguably found their voices and synchronously created their own unique poetic language and tradition that was not merely carved out from the corpus of their male counterparts.

Yet, even as they found their voices most scholarship over the last twenty years has sought to find their names – to understand their place in society, and make sense of their words and songs in terms of their various lifestyles. In a nutshell, the vast amount of critical attention the trobairitz have elicited in recent years constantly seeks to historicize them, privileging a biographical component to their writing. However, this is no easy feat, and with each new discovery there comes debate where academics argue against the newest attributions of identity, often in light of contradictory evidence or even lack of it.

As is, the number of names attributed to the trobairitz are few, and there is little evidence to even play around with, much less debate. However, I feel the debate started in earnest when the trobairitz’s very existence was challenged, practically erased from the history of the larger Troubadour tradition. Beginning with Pierre Bec’s assertion that there were no instances of female authorship (feminite genetique, as he distinguished authorship from merely the female voice, feminite textuelle) in twelfth and thirteenth century northern France, the hunt for female composers was set off. Nevertheless, even as scholars searched out possible medieval female writing there also appeared to be an unmistakeable acquiescence to Bec’s findings that resulted with these female figures left existing in a world of limbo – Shrodinger’s trobairitz.

(note: yes, the trobairitz are originally female poets from the South of France, but I believe current research brings to question the limitations of their spheres, and in subsequent pieces to be posted throughout the next months I will explore their influence across longitudinal borders, which should place into context my intermixing between the hemispheres of France).

From Bec’s assertion sprung numerous others outlining the impossibility of female writing. Either women were simply inept at poetry, or the question would arise as to why they would want to disturb the status quo of the predominantly male Troubadour tradition that placed them upon pedestals, forgetting the attributes ascribed to women placed them upon false pedestals reserved for poor creatures who needed vainglory above all else.

Yet, as more and more probing took place, it became apparent that these early assertions were inaccurate, and female troubadours, to be later referred to as the trobairitz, had thrived in northern France, and southern France, …and Spain, …and Italy. Unfortunately this created the other side of the spectrum where not only did these poetesses exist, but they suddenly existed everywhere, and in large quantities. One of the determining factors for considering female authorship at one point was the appearance of the feminine pronoun in the first person within the work – a cringe-worthy method that quickly created an overabundance of female attributed poems (as I previously discussed such poems created by men, namely Clement Marot).

However, while Bec asserted women in northern France were most certainly not composing poetry, he oddly did not argue a similar case for women of other nationalities. This leads to an entirely new paradox where women were seemingly composing works across Europe in the Middle Ages, except in norther France, where even Bec agreed they were most certainly performing the poems men wrote. What I immediately noticed in this rather convoluted argument was his very precise delineation between authorship and performance where the two acts were irrevocably polarized. If you have been following my female scribe and my trobairitz posts, then you will recall that this distinction if ultimately faulty. Through the process of recreation via any medium, be it written, sung, or simply spoken, there is an inherent mingling into the world of editing. I would never take this argument so far as to posit that these songs should be attributed to women simply because they changed a few words, or even improved the meter, or flow. Withal, when works are appropriated and reconfigured to convey novel ideas, then the work no longer belongs wholly to the original author.

Last time Beatritz de Dia served as the example of appropriation in her “A chantar m’er” as she strategically and wittingly railed at her lover, far outside the perameters of the Courtly Love she was supposedly mimicking, and sounded much more like our modern day H.D. Still, as I constantly use the term “appropriate,” an appropriate French idiom flies to mind, “appeler un chat un chat” (roughly, “let’s call a spade a spade”), and let us refer to “appropriate” as what it really is, “to steal.” Recalling Helene Cixous double entendre verb, voler, it is precisely through such theft of patriarchally dominant methods of communication that women can fly, or even better, soar. Thus the trobairitz took the concepts of Troubadour poetry and flew with them.

Currently I am working on translating two more trobairitz poems, not because I don’t like the translations already circulating, but because I feel most comfortable with a work once I have devised various ways of interpretation that capture the different nuances each word choice has to offer. William Padden’s work on Castelloza is presently guiding my translations as her and Azalais de Porcairagues (who is slightly more elusive) are the two poetesses I want to focus on momentarily.

(Azalais de Porcairagues, BnF MS 854 f. 140)

(Azalais de Porcairagues, BnF MS fr. 12473, f. 125)

(same as above)

Sources:

Bec, Pierre. Ecrits sur les troubadours et la lyrique medievale.

Bec, Pierre. Trobairitz’ et chansons de femme.

Bogin, Meg. The Woman Troubadours.

Bruckner, Matilda Tomaryn. “Fictions of the Female Voice: The Women Troubadours.”

Gaunt, Simon. “Poetry of Exclusion: a Feminist Reading of Some Troubadour Lyrics.”

Paden, William. The Voice of the Trobairitz: Perspectives on the Women Troubadours.